Really kept busy moving around on a return visit to New York & Brooklyn this early May with always so many things to see and do. Culinary adventures were at the top of the list but also enjoyed art (our fav The Frick Collection on East 70th with anticipated expansion in 2020 including a second floor) and theatre (the inspiring new musical Come From Away is highly recommended). Enjoyed two special expensive menu dinners at the upscale Le Bernardin & Per Se that are both deservedly lauded but some of the best values are truly worthwhile checking out as well. Impossible to make a list that doesn’t go on forever but here is your scribe’s Top 5 to include in a forthcoming trip:

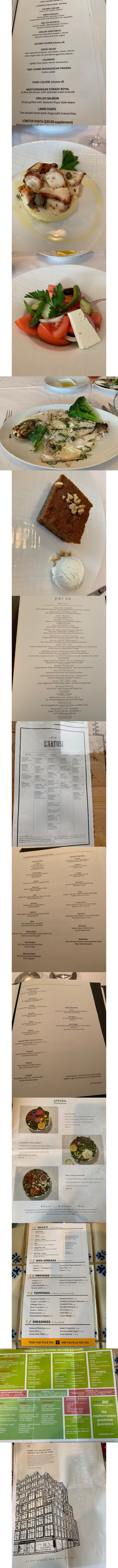

1. HUDSON YARDS: What a an architectural wonder and fun place to tour. Truly spectacular. Be sure to include a walk along the nearby elevated greenway park The High Line either before or after. Our fav from Las Vegas Milos has opened on the 5th floor of Hudson Yards. Recommend the weekend prix fixe lunch special of 4 superb courses for $57 including sensational starter of grilled octopus with yellow split pea fava and main of the whole grilled sea bream. Many shops to visit in the centre but note the new essential oils at MUJI. Good lesson to practise your wine smelling skills with their pure plant materials of flowers, leaves & fruit misted into therapeutic aromas. Interesting range of many from citrus ones (orange & yuzu), herbal (eucalyptus & rosemary) and floral (geranium & lavender).

2. WORLD TRADE CENTRE: A must but so many things to see. Amazing to walk through it all with the wide open spaces and experience the overall feel. So many classy shops in the Brookfield & Westfield Centres. Also like the food opportunities and happy hour specials (5-7pm) especially at extremely popular Eataly. Their Vino E Grano restaurant inside has wonderful Italian food (yummy home made tagliatelle with fresh porcini mushrooms) plus most drinkable wine special choices at only $30 a bottle for an early dinner before the theatre.

3. AN ITALIAN RESTAURANT – L’Artusi: So many fantastic Italian choices. Can’t really go wrong. Our fav is L’Artusi at 228 west 10th where all the dishes and the service sings – a delicious Ricotta Tortelloni with morels, peas, favas, and pecorino. Sensible wine prices by the glass like $16 Aglianico.center

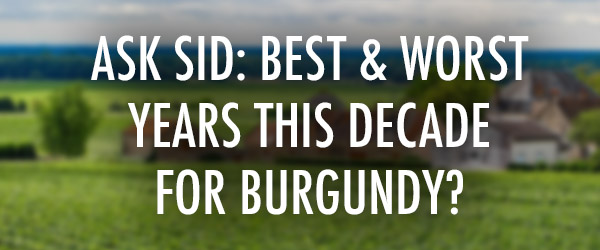

4. LUNCH OF A TRENDY MIX YOUR OWN BIG HEALTHY BOWL: Boy are these places ever crowded. So many to choose from but Cava on 42nd is always jammed with a patient fast moving line-up. Tasty menu of ingredients starting with a base of grains or greens with your picks from there. Look at the attached menu. Two other chains your scribe also recommends with a similar concept are SweetGreen & Nanoosh. Excellent healthy value trendy lunch for sure around only $10+.

5. STARBUCKS RESERVE ROASTERY: You may or may not downgrade the quality of Starbucks coffee since it opened in 1971 at the Pike Place Market Seattle. But you will be impressed to see their showcase that is both a workshop and a stage at 61 Ninth Avenue in New York. WOW. Coffee roasted on site, artisanal breads, pastries, and even pizzas traditionally baked at Princi Bakery, and even cocktails at Arriviamo Bar. Locals take home a bag of better Starbucks Reserve coffee straight from the roaster Scooping Bar. What a necessary tourist tour for the foodie to see.

Find your own unique New York food experience. Please post it.

You might also like:

|

|

|