By Joseph Temple

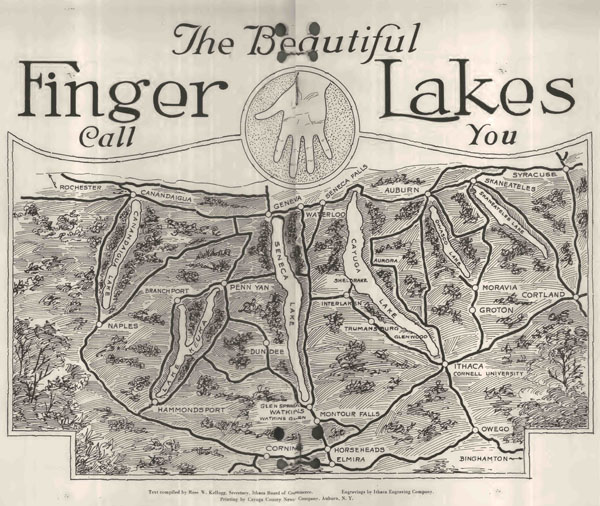

As some of the Finger Lakes were being connected to the Erie Canal, Judge Lazarus Hammond, realizing how prosperous this new trade route could be for the entire region, decided to develop a port on the southern tip of Keuka Lake. Also known as “Crooked Lake” due to its Y-shape, the area became home to a small village named Hammondsport in honor of its financier. And for several decades, this part of Upstate New York, which included numerous vineyards, was essentially German in character. With local winemakers such as Johann Weber, Hiram Maxfield and Mathias Freidell, it was no surprise that the Finger Lakes also became known as an “American Rhineland.”

Then came the Champenois!

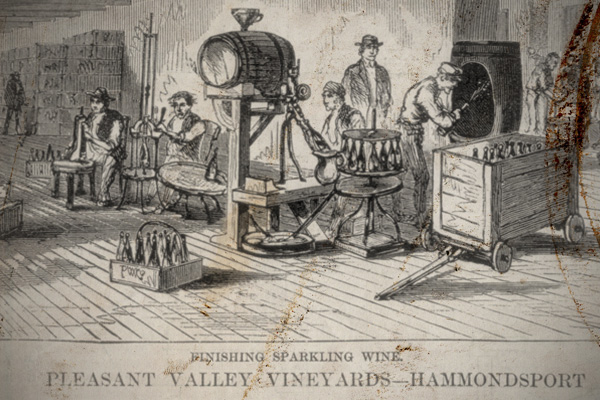

The first to arrive in 1857 was Charles Davenport Champlin who quickly saw many similarities in climate, soil and drainage between his native land in France and the cool countryside of Western New York. With the hills near Keuka Lake providing shelter for the surrounding vineyards along with the late frosts, the prophetic Champlin thought the region was ideal for producing sparkling wine. Four years later as America began fighting a brutal Civil War, he and a dozen other men established U.S. Winery License No. 1—a company created “to produce native wines,” which soon became The Hammondsport and Pleasant Valley Wine Company. Unfortunately, the bubbles that Champlin created for the first couple of years were largely lackluster, requiring him to send in some reinforcements.

Over the next decade, two hired guns—Joseph and Jules Masson—were employed by The Pleasant Valley Wine Company to hopefully put them on the map. With their success in helping to create a sparkling empire in the state of Ohio for Nicholas Longworth, Champlin hoped the two French experts could replicate their accomplishments in Hammondsport. They would not disappoint.

The first successful vintage came in 1870 by using a blend of Catawba and Delaware grapes. Taking this Vitis labrusca combination to Marshall Wilder, the head of a Boston agricultural society, Champlin asked for his opinion on what to call this sparkling wine. After sipping it at a dinner party, he declared it to be the greatest champagne in the entire Western continent and a legend was born! Three years later, a tidal wave of publicity occurred at the 1873 Vienna Exposition where the “Great Western Champagne” won first prize. This triumph, along with top honors in Brussels and Paris, allowed Pleasant Valley to market its sparkling wine as award winning for the next hundred years.

With Champlin blazing the trail, others followed suit and by the end of the nineteenth century, more than fifty wineries around the Finger Lakes were producing bubbles on a grand scale. At one point, historians estimate that over seven million bottles were being sold annually with an astonishing 90% of all American sparkling wine coming out the Hammondsport area. Great Western champagne was taking off!

Of course, this name infuriated the Champenois who to this day believe that no sparkling wine made outside the Champagne region can use that designation. Hoping to put a stop to what they considered to be a flagrant misuse, the French delegation at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference slipped in Article 275, which sought to protect Champagne from others who incorrectly used that name on their labels. But since the United States Senate failed to ratify the Treaty of Versailles, American winemakers were free to use the name champagne for the remainder of the twentieth century. And what must have been seen as rubbing salt in the wounds of the Champenois, The Pleasant Valley Wine Company successfully lobbied the U.S. Post Office to rename the hamlet where they were located. After that, they could now market their Great Western champagne as being from “Rheims, N.Y.”

Today, Hammondsport, New York is largely seen as the cradle of aviation, being the birthplace of Glenn Curtiss, an early pioneer in the history of American flight. But with the breakout success of Great Western champagne in the nineteenth century, Hammondsport should also be regarded as the cradle of American viticulture.

Sources:

Falk, Laura Winter. Culinary History of the Finger Lakes: From the Three Sisters to Riesling. Charleston: The History Press, 2014.

Figiel, Richard. Circle of Vines: The Story of New York Wine. Albany: SUNY Press, 2014.

Kladstrup, Don & Petie. Champagne: How the World’s Most Glamorous Wine Triumphed Over War and Hard Times. New York: HarperCollins, 2005.

Merrill, Arch. The Lakes Country. Rochester: Louis Heindl & Son, 1944.

Pellechia, Thomas. Over a Barrel: The Rise and Fall of New York’s Taylor Wine Company. Albany: SUNY Press, 2015.

You might also like:

|

|

|