Thanks to Robert Henderson of the Toronto Branch for sending me this audio file of André Simon discussing the importance of wine. Recorded during the late 1960s or early 1970s, his message proves to be relevant to this day.

Enjoy!!

Thanks to Robert Henderson of the Toronto Branch for sending me this audio file of André Simon discussing the importance of wine. Recorded during the late 1960s or early 1970s, his message proves to be relevant to this day.

Enjoy!!

As a student of the history of newsreels, I was excited to discover this Hearst-Metrotone (renamed News of the Day in 1936) gem which was first screened in 1933, titled “Prohibition’s Reign Ends!” For those who have studied the era (or fans of the HBO series Boardwalk Empire), you’ll recognize all the names and terms synonymous with this period: Andrew Volstead, Al Smith, Rum Row, wets, drys, bootleggers, speakeasies, the Real McCoy, etc..

Of course, it was no coincidence that as this period in American history was ending, André Simon was busy establishing the first IW&FS branches in the United States. Since you no longer needed a doctor’s certificate to drink wine legally, America became fertile ground (no pun intended) for the International Wine and Food Society. You can watch a brief history of our society by clicking on the video below:

Cheers!

By Joseph Temple

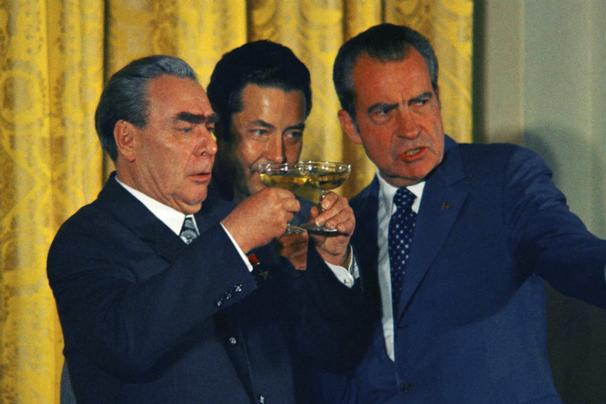

“This is a masterpiece,” declared Richard Nixon over the phone to Henry Kissinger. Referring to the Prevention of Nuclear War (PNW) agreement between the United States and the Soviet Union, he and Leonid Brezhnev had just eased Cold War tensions significantly through the president’s foreign policy known as détente. And to celebrate the historic 1973 summit that moved everyone a step closer to world peace, both leaders sipped Champagne in a brilliantly orchestrated photo-op.

It was an ironic choice since neither leader cared much for the bubbly – Nixon being a Bordeaux man and Brezhnev more at home with a bottle of Russian Vodka. But in front of the cameras, they both drank while hundreds of invited guests applauded their diplomatic breakthrough.

President Nixon and Leonid Brezhnev toast with Champagne after signing a series of agreements in

the East Room of the White House on June 21st, 1973. (Photos Credit: National Archives)

“All these things this week are good,” Nixon told his daughter Julie. “It gets people thinking about something else.”

That “something else” was the Senate Watergate Committee. With Brezhnev’s visit to the United States, all hearings had been temporarily postponed. But as soon as he left for Moscow, they were ready to go back into full-swing, starting with the explosive testimony of former White House counsel John Dean.

However, on the other side of the world, it seemed that Nixon had committed an international Saturday Night Massacre when information about the menu from his state dinner with Brezhnev crossed the Atlantic.

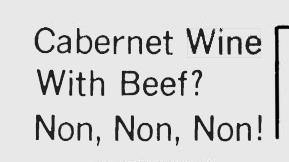

A “gastronomic heresy” decried L’Aurore, a Parisian newspaper. The crime: Cabernet Sauvignon had been served with beef, a clear mismatch according to the French. “Most assuredly, the association of a filet de boeuf bordelais with a sauvignon wine would make a gourmet faint in France.”

Adding insult to injury, the menu contained phrases in “Franglais” like “supreme of lobster en bellevue.” And calling for lobster to be served with a remoulade sauce struck the French as very odd considering it was sauce only put on celery root.

It wasn’t the first time Nixon’s wine selection created controversy. During the first month of his presidency, he enraged domestic wine producers by uncorking a bottle of French Champagne at an official White House function. Since the Johnson administration, only American wines were served at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue and for a Californian like Nixon to drink French wine in front of the television cameras was treasonous.

(Right) The French Press was outraged at the food and wine pairings for the State Dinner honoring

Brezhnev’s visit. (Left) Brezhnev, Richard Nixon and First Lady Pat Nixon attending the dinner.

But was it French pride over all things food and wine that caused this cause célèbre? Or was there a more conspiratorial motive for blasting this White House selection? One American newspaper hypothesized:

“We all know that West European countries fear their influence in world affairs will diminish as the United States develops closer ties with China and the Soviet Union. Now supposed that Brezhnev became convinced that Nixon had served him an inappropriate wine. That surely would be a a major setback in the effort to improve relations between the two countries. At the same time, it would enhance the prestige of France – making it appear that French advice on wine selection is indispensable to the conduct of American foreign policy.”

Whether it was a well orchestrated plot by the French government to derail Nixon’s policy of détente or not, a few journalists did rush to the president’s defense. “I don’t know whether Nixon was exquisite in serving a Cabernet with beef because I never tried the combination,” wrote syndicated columnist Andrew Tully. “Palates differ … you can advise an American on wine, but never, never a Frenchman.”

So what do you think of this little Cold War footnote? Successful gastronomic experimentation or colossal failure?

By Joseph Temple

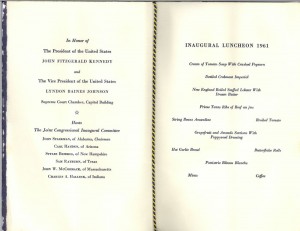

On the same day Americans were summoned to ‘ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country’, John Fitzgerald Kennedy sat down for his first meal as 35th President of the United States. After starters of creamy tomato soup and deviled crab meat Imperial, the next course catered specifically to the new Executive Branch of JFK and LBJ: New England boiled stuff lobster with drawn butter and prime Texas ribs of beef au jus.

This was the beginning of Cuisine à la Camelot.

For a thousand days, 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue became the epicenter for lavish state dinners and meals that symbolized early 1960s enthusiasm. Historian Marie Smith in her 1967 book Entertaining in the White House writes, “Not since the days of Dolley Madison had the White House been the scene for such brilliant entertaining as was done by First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy and her history-conscious husband, John F. Kennedy – and not since the days of Thomas Jefferson, America’s first gourmet of renown, had more serious thought been given to White House standards of food and drink.”

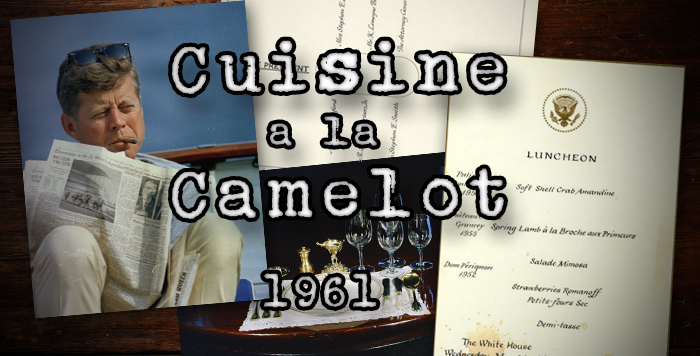

INFLUENCES: Julia Child (left), the world’s first “celebrity chef” popularized French cuisine with her cookbook Mastering the Art of French Cooking (2nd from left). Spy James Bond drinks Dom Pérignon ’46 in the 1955 novel Moonraker (2nd from right). Kennedy was a huge fan of author Ian Flemming and his 007 character, who debuted on the big screen in 1962’s Dr. No where Sean Connery’s character tells his captor after trying to break a bottle of Dom Pérignon ’55 over a guard’s head “I prefer the ’53 myself.” (right)

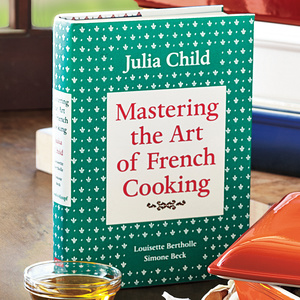

It was 1961 and Julia Child was at the height of her popularity after releasing volume one of Mastering the Art of French Cooking. Anything French was distinctly fashionable throughout American culinary circles. So it is no surprise that many dishes served to the Kennedys and their guests paid tribute to White House Chef René Verdon’s Parisian roots. With casseroles of the 1950s clearly out-of-style and the ration books of the 1940s a distant memory, the new administration was a clear shift from the previous era symbolized by Truman and Eisenhower.

Chef Verdon took over an operation previously run by caterers and Navy stewards not known for producing quality dishes and transformed it into the modern White House kitchens we know today. Promoting local fresh foods before it became fashionable, his kitchen staff cemented the Kennedys as hip culinary trend setters – resulting in many suburban housewives making soufflés, pâtés, and pork rillettes for their own dinner parties.

Debuting with trout cooked in Chablis, roast fillet of beef au jus, and artichoke bottoms Beaucaire, Chef Verdon’s meal for JFK and British Prime Minister Harold MacMillan made the front-page of the New York Times, prompting Craig Claiborne to write, “there was nothing like French cooking to promote good Anglo-American relations.”

For the visit of Korean General Chung Hee Park, a lunch that can be described as classical upscale French cuisine meets Southern style cooking was served. It featured snails in brown butter parsley sauce, barbecue chicken, potatoes, and creamy mushrooms. A simple yet elegant lunch filled with the charming rustic touches of an open grill.

(Left) White House Executive Chef René Verdon (third from left) and members of the White House kitchen staff pose with an assortment of cookies. The kitchen went through numerous renovations in the 20th Century. The kitchen in 1901 (middle) and in the 1950s (right).

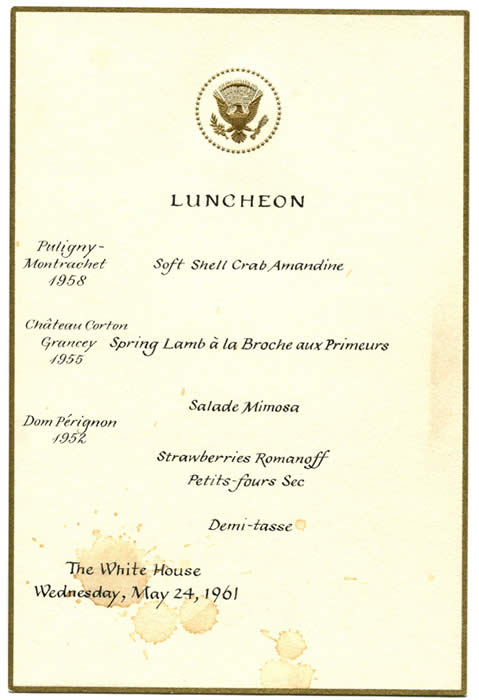

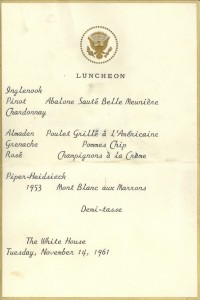

And during most of 1961, the Kennedys drank almost exclusively French Wine and Champagne. An example wine menu from the 1961 White House gala in honor of former President Harry Truman: 1955 Château Gruaud-Larose – an underrated vintage of pure cedary Cabernet second growth, St. Julien styling, 1958 Puligny-Montrachet Les Pucelles – a Chardonnay with pronounced notes of creamy buttered apples, and 1952 Cuvée Dom Pérignon Brut.

It is no surprise that Jack Kennedy loved Dom — the same drink consumed by a fictional spy named James Bond in the Ian Flemming novels that the president devoured. And while Agent 007 preferred a ’53, the 1952 served at the White House was a long aging firm rich year when there was still some barrel fermentation for complexity.

In an era before Twitter, cell phone cameras, and a tabloid media, the press largely complied with the Kennedys’ request that the wine list from White House functions not be printed in the next day’s newspapers. However, when word began to leak that no American wines were being consumed, public pressure convinced them to start serving wine from the United States and more specifically California – a region that hadn’t yet exploded into the mainstream.

“We served only French wines in the beginning,” recalled Kennedy White House social secretary Letitia Baldrige. “But about six months into the Administration there was such a hue and cry about it that we began to serve mostly American. We would serve one good French – either a wine or Champagne – but the other two wines would be American. And sometimes we would serve an Italian wine such as a Soave Bertani.”

At the table with his guests however, Kennedy was not always on top of his game in terms of dinner diplomacy. When Monaco’s Prince Rainier III and his movie star wife Grace Kelly stopped by in 1961, the president worried about mispronouncing his name “Prince Reindeer.” Months earlier, he had enraged Canadian Prime Minister John Diefenbaker when at the White House, he called him in front of the entire press corps “Prime Minister Dee-fen-bawker.” He did not want an incident like that to occur again.

(Left, Middle) Prince Rainier III and Princess Grace of Monaco Arrive at White House for a Luncheon in Their Honor. (Right) The menu for their visit.

But as they enjoyed their light lunch of Salade Mimosa, Soft Shell Crab Amandine, and Spring Lamb à La Broche Aux Primeurs, JFK accidentally responded to the Prince with “Prince Reindeer” in his signature Bostonian accent. Thankfully, the gaffe was short-lived when in an interview four years later, the Princess recalled every detail of the lunch including all the dishes she had eat – a clear sign of success for Kennedy’s kitchen staff!

Away from Washington, JFK and Jackie were treated to an impressive feast at Buckingham Palace. It was 5 June 1961 and a little over a month since the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion. The previous day in Vienna, Kennedy had stared down Nikita Khrushchev in a high-stakes game of nuclear diplomacy over Berlin – setting the stage for future confrontations in 1962. So with Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip by his side, the president ended his European charm offensive by enjoying some very royal dishes.

(Left) Prince Philip, Jacqueline Kennedy, Queen Elizabeth and JFK pose for a photo at Buckingham Palace. (Right) The menu from that event.

Beginning with creamy pea soup, hollandaise sole garnished with asparagus second, lamb and buttered green beans was served as the main course. This seemingly simple menu would have been masterfully executed with classic French techniques to impress Her Majesty and guests. Not only did the many refined sauces showcased make precision timing critical, the showstopping Grand Marnier soufflé served for dessert is one of the most difficult dishes to execute for such an expecting crowd.

Clearly, 1961 served as transformational year for food and wine served in the White House; 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue was now on the cutting edge of the culinary arts. An exclusive team of superb cooks, headed by a French chef, would shape food and wine served even today to the modern Presidency.

Please have a look at the pictures and menus on this page by clicking to enlarge them. Also, vote for what you think is the best dish served during this year and leave your comments. Special thanks to Sid Cross who helped to provide information on the wines.

|

It was at the height of the Cold War and nuclear energy was everywhere. As numerous power plants were built across North America, the USS Nautilus became the world’s first submarine to be fueled by the atom. Considered both the safest and cheapest way to electrify towns and cities, experts predicted that you would no longer have to meter homes due to nuclear power’s outrageously low costs.

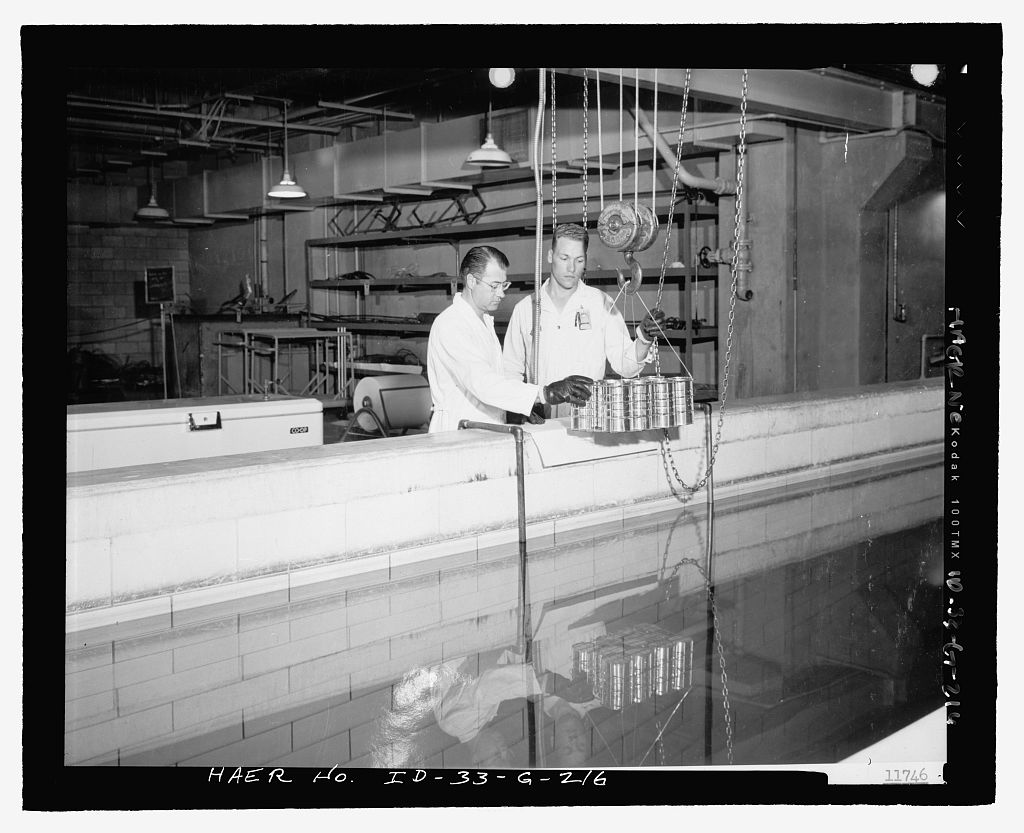

Workers pose for a Gamma Irradiation Experiment. Cans of food will be lowered

Workers pose for a Gamma Irradiation Experiment. Cans of food will be lowered

to canal bottom, where MTR fuel elements emit gamma radiation.

So during this period, it was only natural that atomic science crossed paths with the food we eat. Starting in 1953, the United States Army along with scientists at MIT began testing out whether using specific dosages of ionizing radiation would slow down or possibly eliminate the spoilage of food by destroying certain bacteria in it. And although the technology had existed for nearly half a century before, Cold War geography now made food preservation a top government priority.

As the Korean War winded down and the American military extended its footprint across the globe, the issue of keeping food fresh for soldiers and personnel on the front lines was vital. If war broke out in Berlin, Budapest or Beirut, meals could be brought from the other side of the globe just as fresh as the day they were picked or cooked. With irradiated food, expiry dates could go from days to months — even without refrigeration. Food storage would be revolutionized for military and civilians alike.

More than half a century later, many of the foods and spices we eat use irradiation. And while consumers have raised concerns about the safety of irradiating food, often confusing it with being radioactive (it’s not), studies have showed that more and more people are opening up to this concept. What’s your thoughts? Pro or con?

The international Radura logo, used to show a food has been treated with ionizing radiation.