As the world’s fourth largest producer of wine, California’s vineyards now generate over 120 billion dollars annually and are responsible for three out of every five bottles purchased by Americans. Internationally, 47.2 million cases were exported to 125 countries in 2012 – up 51% from a decade before. Never has the Golden State been more of a viticultural superpower than it is today.

But if you’ve studied the region’s history, you know that there have been many trials and tribulations on the path to prosperity. So for this week, have a look back at seven decisive turning points that helped create the wines of California that we enjoy today.

blank

blank

Whether it was the early studio moguls that created Hollywood or Okies escaping the Dust Bowl during the Great Depression, California has historically served as a magnet for people looking to create a better life financially. And during the mid-19th century, thousands of Americans migrated west when word spread that there was gold to be found. Almost overnight, the population of San Francisco exploded as the first “forty-niners” arrived in 1849 with hopes of striking it rich. However, when it all ended in 1855, the only ones making any money were the people selling shovels.

Unable to prosper in the gold fields of Northern California, many migrants turned to another potential source of revenue – the terroir of Napa and Sonoma. Capitalizing on the region’s fertile soil and ideal climate, many traded in their pans for a new life as winemakers. Some of these famous names included Charles Krug, Jacob & Frederick Beringer and Agoston Haraszthy who advocated tirelessly for the blending of European grapes with native rootstocks.

blank

blank

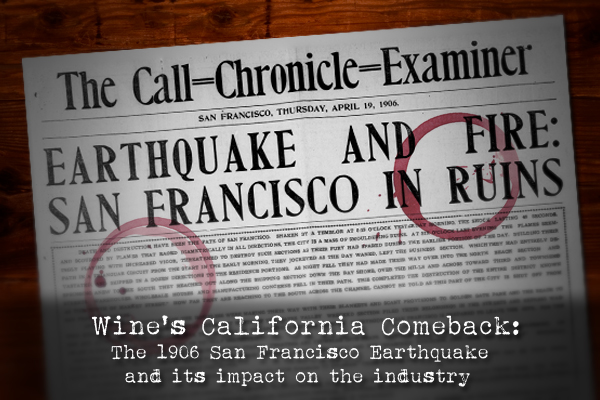

Today, it might seem strange to think of foggy San Francisco as the wine capital of America. But at the beginning of the twentieth century, with its wealthy wine merchants and close proximity to both rail lines and the Pacific Ocean, “The Paris of the West” controlled the production and distribution of nearly all Golden State wines. Home to the powerful California Wine Association (CWA), its headquarters stored millions of bottles for shipment across the entire United States.

But in 1906 when a catastrophic 7.8-magnitude earthquake left the city in ruins, the wine industry learned a painful lesson on the dangers of centralization. With nearly 10,000,000 unsalvageable gallons flowing through the streets of San Francisco, a major restructuring occurred resulting in bottles being stored more closely to the vineyards, creating what we now know as California wine country.

blank

blank

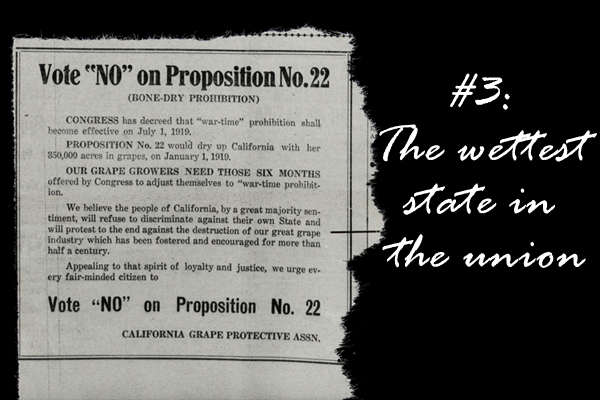

Having almost ninety thousand acres dedicated to grape growing by 1920, Sacramento lawmakers understood how vital the industry was for the state’s economy. It was no surprise then that Californians defeated four separate ballot initiatives to enact statewide prohibition prior to the Volstead Act. With nearly seventy-five million dollars a year at stake and large Irish and Italian populations in San Francisco that were passionate about wine, those favoring temperance were never able to achieve much success in the Golden State – that is until the forces from Washington DC stepped in.

blank

blank

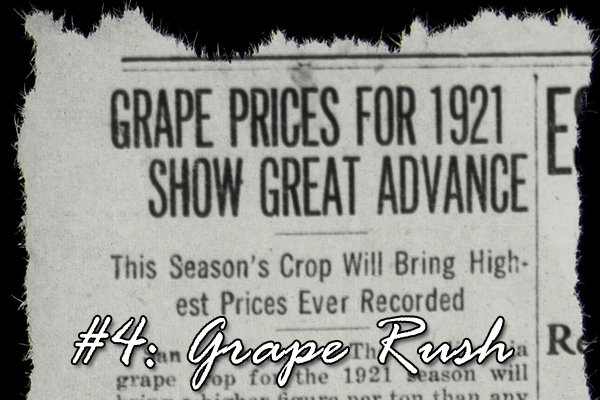

Looking at back the many flaws of prohibition, one specific loophole that made millionaires overnight was a provision allowing each household to produce two hundred gallons of fermented fruit juice per year. Suddenly, thirsty Americans everywhere became amateur winemakers eager to reap in huge profits by selling their surplus around the neighborhood. All they needed now was a steady supply of grapes.

“Grapes are so valuable this year that they are being stolen,” wrote the St. Helena Star. A new kind of gold rush had started in California as one acre of vineyard land shot up from $100 to $500 by 1921. A year before Prohibition, 9,300 carloads of grapes traveled from California to New York. By 1928, that figure had more than tripled.

blank

blank

Unfortunately for the profiteers, Zinfandel and Chardonnay grapes didn’t travel well in freight cars across the country. But with prices going through the roof, a new source that could maximize value was desperately needed. And that source went by the name Alicante Bouschet, a grape that made for inferior wine with one novelist ranking it somewhere below the gooseberry. However, it had numerous advantages that made it perfect for the lucrative east coast markets.

For starters, unlike other varietals, Alicante grew in abundance. And its thick, durable skin guaranteed that it could withstand the long train ride east. On top of that, its dark red texture – even after three pressings and numerous dilutions made it look deceptively decent to all the novice winemakers and drinkers sprouting up across the country.

So throughout California, Alicante became the new fool’s gold as growers and traders cashed in on this new miracle grape. Quantity trumped quality as generations of experienced vintners looked on in disgust as their craft was being tarnished for the almighty dollar.

blank

blan

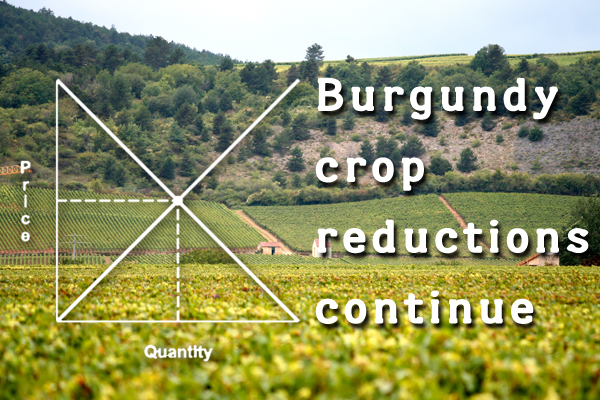

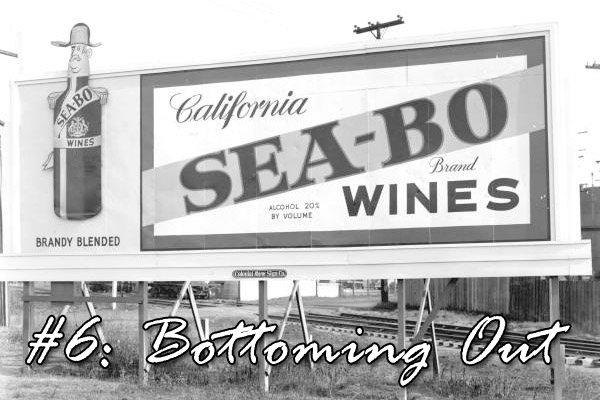

Prohibition may have ended in 1933 but the thirteen year absence of experienced winemakers cultivating the land would leave a terrible impact across the state. And as the Alicante bubble burst, California’s reputation as a promising wine region went up in smoke. During the postwar period, the state became infamous for producing cheap fortified blends that were the preferred choice of winos looking for nothing more than a quick buzz.

How bad did it get? By 1964, the tonnage of Chardonnay grapes in California was so miniscule that the state’s Agricultural Service didn’t even bother tracking it. That’s because for many years, high-alcohol jug wines were the staple of an industry that had hit rock bottom.

blank

blank

In beginning to turn the corner, the University of California at Davis started researching the terroir throughout the state in order to determine the best grapes to plant. The report, issued in 1944 concluded that Napa Valley, which shared a similar temperature to Bordeaux, was the ideal spot to grow Cabernet Sauvignon while Sonoma should focus on Pinot Noir and Chardonnay. Titled “Composition and Quality of Musts and Wines of California Grapes,” this study would lay the groundwork for a wine making renaissance in the Golden State.

Putting this document into action, the early 1960s saw a whole new generation of amateur winemakers arrive with the goal of producing award winning vintages. And within a decade, all their hard work would pay off as the quality improved dramatically. The proof came in 1976 when California defeated France at a blind tasting held in Paris, an event that was later the subject in the 2008 motion picture “Bottle Shock.”

With branches in Los Angeles, Laguna Beach, Chula Vista, La Jolla & Pasadena, the International Wine & Food Society has a strong presence across California.

Sources:

MacNeil, Karen. The Wine Bible. New York: Workman Publishing Company, 2000.

Okrent, Daniel. Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition. New York: Scribner, 2011.

Taber, George. Judgement of Paris: California vs. France and the historic 1976 Paris tasting that revolutionized wine. New York: Scribner, 2005.

California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Online Catalog.

Online Archive of California.

Florida Memory Project.

You might also like:

|

|

|