By Joseph Temple

From East Los Angeles to the suburbs of Middle America, Mexican cuisine is ubiquitous all across the United States. Whether you’re buying a can of chili at the grocery store, grabbing a quick bite from the local Taco Bell, or enjoying some sizzling fajitas and a frozen margarita, Mexico has definitely made an enormous impact on our palates. Ever since America took its first bite, from tamales to tacos, the multi-billion dollar demand for Mexican food has shown no signs of slowing down.

So how did burritos and chimichangas conquer America? Given a contentious history that’s lasted for more than a century between the two nations, it’s almost ironic that Mexico’s delicacies have been able to cross the border with such ease. “Mexican food has entranced Americans while Mexicans have perplexed Americans,” writes author Gustavo Arellano. “In the history of Mexican food in this country [the United States] you’ll find the twisted fascinating history of two peoples, Mexicans and Americans, fighting, arguing, but ultimately accepting each other, if only in the comfort of breakfast, lunch and dinner.”

Tackling such a fascinating subject in his book Taco USA: How Mexican Food Conquered America, Arellano, author of the popular syndicated column titled “¡Ask a Mexican!” sets out to uncover a history that has been largely untold and forgotten. While some Americans are under the impression that Mexican food only became popular after the Second World War as chain restaurants and supermarkets dominated the suburban landscape, the author combats this erroneous narrative with a timeline that is illustrated by a wealth of primary source material.

It is a story that began after the Mexican-American War when Yankee tourists traveling to San Antonio tried something known as chili con carne (later shortened to just chili). And serving this exotic dish from a boiling hot cauldron were women dubbed the “chili queens”—the first superstars of Mexican cooking according to Arellano. “This meal … will be an event in your gastronomic experience,” according to an article in Scribner’s from 1874. Spreading like wildfire across the country, the popularity of chili con carne was only matched by another Mexican dish called the tamale.

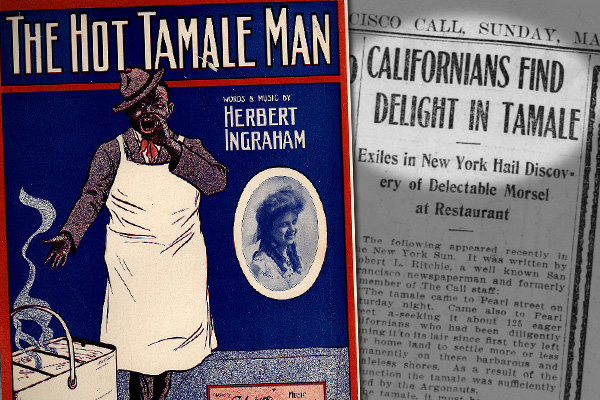

Images courtesy: Duke University Libraries,

California Digital Newspaper Collection

Vended by individuals wearing white coats and aprons, these instantly recognizable tamale men or tamaleros quickly became a staple in late nineteenth century America. Selling their product from a large pail in what became a precursor to the modern-day food truck, everything from popular songs to plays and films showcased this seemingly larger-than-life figure. “Hot tamaleees! Hot tamaleeeeeees. If you’re growing old/hot tamales will save your soul,” according to the lyrics of one song.

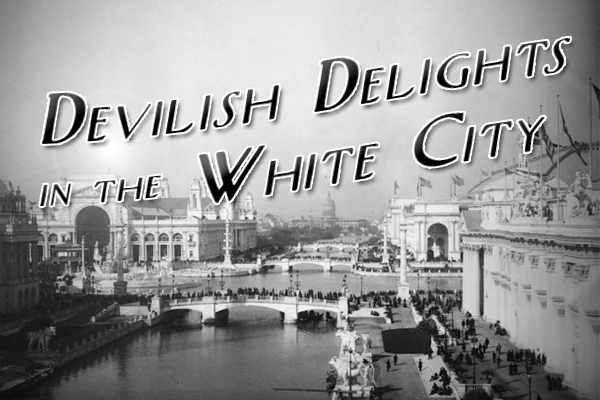

In finding a turning point for Mexican food, the author points to the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, held in Chicago, Illinois. An event that was the subject of Erik Larson’s 2003 mega bestseller The Devil in the White City, this world’s fair is also remembered as the place where the tamaleros became a part of American popular culture as they sold countless tamales to millions of hungry fair-goers. Additionally, with Chicago being the epicenter of the canning industry, it is also where chili in a can debuted, ending the reign of the chili queen but making the dish accessible to millions of new customers.

Moving on to the twentieth century, a plethora of new dishes would enter the mainstream of American fare; the story of the taco, the burrito, and the tortilla chip are all highlighted throughout the book. But more important are the stories dealing with those restaurant tycoons who provided the all-important venue for non-Mexicans to experience this fare. And despite what you might think about its menu, there is no denying what Taco Bell did in blazing the path for all future chains. According to Arellano, this Southern California fast food giant “showed other Americans that their countrymen hungered for Mexican grub sold to them fast, cheap, and with only a smattering of ethnicity.” Designing its restaurants with a mock adobe exterior and tiled roofing to look like a mini-mission, the author contends: “It was a slice of fantasy Mexican California plopped into suburbia, and a motif that has influenced the aesthetic designs of Mexican restaurants ever since.”

As people transitioned from fast food to sit down restaurants, one cannot also stress how vital the frozen margarita machine invented by Mariano Martinez was to the explosion of Mexican food. Emphasizing how revolutionary this device was and is, the author states: “The frozen margarita machine came just as the sit-down Mexican restaurant scene was taking off—really, the surge Chi-Chi’s, El Torito, and others experienced during the 1970s wouldn’t be possible without alcohol to lure in people to casually try the Tex-Mex-Cal-Mex platters the restaurants served almost as asides.”

This, of course, begs the question: what constitutes authentic Mexican cuisine? Throughout Taco USA, Arellano states his view that any food created by a person of Mexican origin fits that bill, whether its Doritos, invented at Disneyland in the early 1960s or fajitas—a dish that has been universalized so much that we no longer think of it as Mexican. While Tex-Mex hating purists might scoff at this notion, the author reminds us that non-Hispanic Americans, in their quest to find true authenticity have lead to many evolving trends like the move away from Doritos chips to more “authentic” Tostitos.

Overall, it is a phenomenal narrative that shows us how far Mexican food has come since the days of the tamale men. When in the early 1990s, salsa was revealed to be the number one condiment, beating out ketchup in what one food critic called “the manifest destiny of good taste,” it was clear that Mexican cuisine had become as American as apple pie. And through an entrepreneurial spirit embodied by companies like Old El Paso and restaurants such as El Torito and Chipotle, rarely does a week go by without the average family eating a Mexican influenced dish. Proving this point, Arellano highlights Brookings, South Dakota, a college town whose Latino population represents less than one percent of its residents. And yet for a city of just over twenty thousand people, there are four Mexican restaurants. Need any more proof?

You might also like:

|

|

|