By Joseph Temple

Today, with oyster consumption at an all-time low across the United States, it may seem surreal to think that oysters, described by James Beard as “one of the supreme delights that nature has bestowed on man” were at one time considered quintessential American fare. That’s right—back in the late 1800s, the average person from Maine to California ate a whopping 660 oysters per year—a figure that was triple the amount of what was being consumed in the United Kingdom!

So why is it that you rarely see anyone eating this seafood outside of Boston’s Union Oyster House or New York City’s Grand Central Oyster Bar? And how did oysters get to be so popular in the first place?

To answer the latter, you need to go back to early nineteenth century when oysters were strictly a local affair. Harvested in places like the Chesapeake Bay, the shelf life of an oyster was short, making it extremely difficult to ship this delicacy to the American interior without spoiling. But with arrival of refrigeration in the 1830s, improved railroad lines, and the canning industry, what was once only available on the coasts could now be enjoyed all over the Midwest too.

Having these technological advances, the supply of oysters skyrocketed in the two decades after the American Civil War. While harvested in numerous spots, the mecca for oyster beds was New York City, specifically the bays of New York Harbor and Long Island Sound. From 1880-1920, as the city’s population exceeded over a million people, New York alone produced approximately 700 million oysters per year. Using techniques that would make modern day ecologists cringe, this rapid depletion led to oysters representing nearly a third of the total value of all U.S. fisheries during this time.

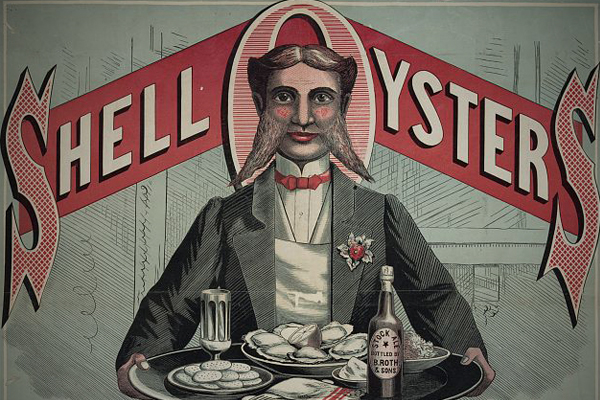

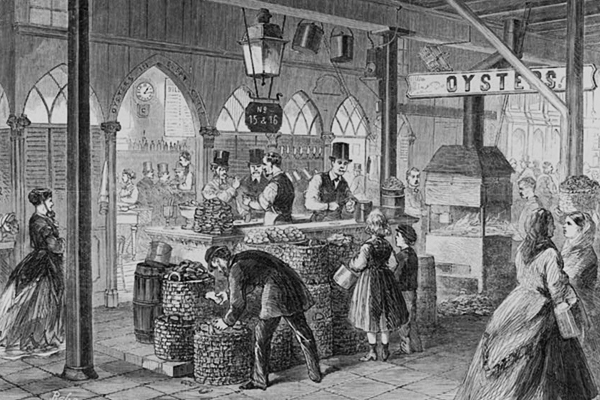

Helping to fuel this full-blown craze by the 1870s was the oyster bar—an American institution that should be studied by every culinary student. With an abundant supply being transported around the country, the cost of oysters was only half the cost of beef per pound, making it the perfect seafood to compliment one’s beer or whiskey. By the 1880s, nearly every city and town had either an oyster bar, an oyster lunchroom, or an oyster cellar, where they were offered to a thirsty clientele the same way pretzels are today. Appealing to both rich and poor, oyster houses could serve them many ways, from broiled and roasted to pickled and scalloped. “Oysters are not only a delicious luxury for the wealthy epicure, but are an economical and wholesome food for those of limited means,” according to one industry-sponsored pamphlet. “They should not be regarded as a rare treat, but as a frequent and appetizing item of regular food supply.”

But how did all this come crashing down? Well, by the twentieth century, oysters received a wave of bad publicity, being blamed for several breakouts of cholera and typhoid, causing demand to plummet. Also, with the enactment of the Volstead Act in 1919, Prohibition had pretty much wiped out the [oyster] bar, a venue where most Americans were getting their supply. Sadly, since this time, very few have survived.

Arguably the most popular food of the 1800s, the oyster, given its rich history really is as American as apple pie. So the next time you want to honor your nation’s culinary past, why don’t you try serving this wonderful seafood. Whether it’s Oyster Soup, Oysters on Toast, or Philadelphia Fry, you’ll take great pleasure in rediscovering a classic dish!

Sources:

Flood, Charles. Lost Restaurants of Seattle. Charleston: The History Press Inc., 2017.

Greenburg, Paul. American Catch: The Fight for Our Local Seafood. New York: Penguin, 2014.

Isa, Mari. (2017, February 23). The Great Oyster Craze: Why 19th Century Americans Loved Oysters. Michigan State University. Retrieved from http://campusarch.msu.edu.

Maruzzi, Peter. Classic Dining: Discovering Americas’ Finest Mid-Century Restaurants. Layton: Gibbs Smith, 2012.

Smith, Andrew F. Savoring Gotham: A Food Lover’s Companion to New York City. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

You might also like:

|

|

|