By Joseph Temple

“Champagne is not a wine,” wrote one reviewer from the nineteenth century. “It is the wine.” Producing the quintessential drink to celebrate everything from wedding vows to winning the World Series, the region of Champagne, with its chalky soil and cold climate has taken on mythical proportions as a place synonymous with happiness and joy. But behind those millions of fine bubbles is a darker past—a past plagued by war and devastation. “The greatest irony of all,” writes authors Don and Petie Kladstrup, “is that Champagne, site of some of mankind’s bitterest battles, should be the birthplace of a wine the entire world equates with good times and friendship.”

The duo that also penned 2001’s best seller Wine and War: The French, the Nazis and the Battle for France’s Greatest Treasure dispels the notion that sequels tend to disappoint with their riveting history Chamapgne: How the World’s Most Glamorous Wine Triumphed Over War and Hard Times. Looking back through the centuries, the Kladstrups’ uncover a past that both wine drinkers and non-drinkers alike will find simply fascinating.

For starters, we learn that in the beginning, the irresistible blend of Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier was a foreign concept to most vintners in the region. Besides being known for producing wool, Champagne was a place to go not for sparkling wine, but for red wine. In fact, the rivalry it had with its neighbors in Burgundy was so intense that had the Champenois not slowly switched over to fizz, an all-out war would’ve broken out between the two competing regions.

Ironically, this gradual shift towards sparkling wine was met with ardent resistance by some of the area’s most iconic figures. Dom Pérignon, a Benedictine monk who is etched in stone as one of Champagne’s greatest winemakers did everything in his power to eliminate the bubbles from his wine, considering them to be a terrible flaw. He was seconded by Louis XIV, a fan of Champagne but a hater of bubbly.

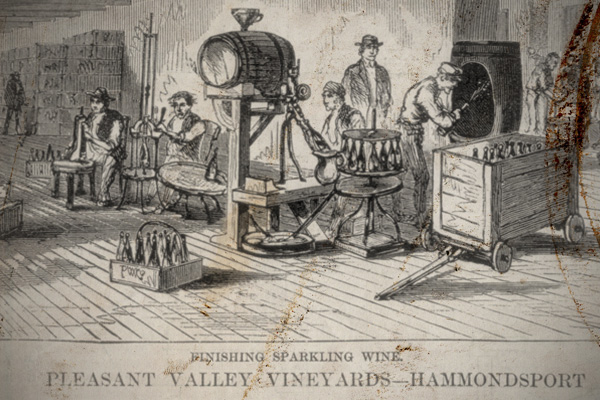

While today the method for making champagne is uniform and rigid, back then, the process was so unpredictable and dangerous that it was commonly called the “Devil’s wine.” Due to the buildup of carbonic gas, the book informs us that winemakers were required to wear a crude version of a catcher’s mask in case a bottle exploded, which was often. And what now seems surreal, prior to 1728, French law required sparkling champagne to be transported in wooden casks for taxation purposes. “Wood destroyed its effervescence,” writes the Kladstrups’. “Its porous nature allowed the gas to escape, resulting in champagne that was flat.” Thankfully, an exception was made for Champagne as the science behind bubbly began to evolve.

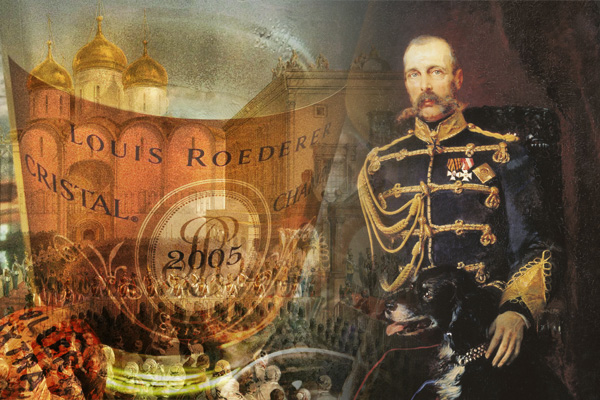

In identifying the key players who made Champagne what it is today, the authors highlight the efforts of Claude Moët, the first winemaker in the region to switch over entirely to sparkling wine. Continuing the timeline, they state: “Louis Pasteur’s discovery of yeasts helped champagne-makers understand what fermentation really is … an enterprising champagne producer named Adolphe Jacquesson invented the bottle washing machine. He also invented the wire muzzle, which replaced the string that had previously been used to hold down corks. William Duetz topped him by developing the metal foil that covers the muzzle and cork.” Last but not least was Barbe-Nicole Ponsardin who invented the process known as remuage (or riddling).

Another fascinating subject of the book deals with the region itself, and how Champagne, until this past century, never saw itself as one monolithic region united under a common purpose of making bubbles. Instead, the Marne, its most prestigious area viewed the Aube as nothing more than a red headed stepchild piggybacking off the former’s reputation. This toxic relationship, in part, led to the infamous Champagne Riots of 1910 and 1911, when local growers rebelled against what they saw as unfair practices from the big houses. Feeling shortchanged by policies requiring that only 51 percent of the grapes used to make champagne had to come from within its boundaries, fans of this wine may be shocked to uncover that apple and pear juice were also sometimes used in place of actual grapes. Describing the chaos in great detail, the reader learns that approximately six million bottles flowed like a river down the streets as numerous champagne houses lay in ruin. The region’s production methods, guided by a strict set of rules and regulations, was born largely as a result of these riots.

Arguably the book’s greatest strength are the two chapters dealing the First World War and its devastating impact on Champagne. Describing the situation, Don and Petie Kladstrup write: “trenches cut through Champagne like a jagged knife, zigzagging across the region and slicing through vineyards. As winter fell and the year drew to a close, the chalky soil of Champagne turned those trenches into a hell of grey, clinging mud.” Those interested in military history will wonder how Champagne ever came back after enduring 1,051 consecutive days of bombing resulting in a loss of half its population—all while its surviving citizens lived for years in underground caves known as crayères. At the same time, when you read quotes from Winston Churchill stating that “Remember gentlemen, it’s not just France we are fighting for, it’s Champagne,” it will have a whole new meaning.

From Dom Pérignon to Champagne Charlie, this book delivers in presenting a concise history of both the region and its people up until the Second World War. Additionally, members of the International Wine and Food Society will also be pleased to know that André Simon’s The History of Champagne is listed in the bibliography, making it a well-researched historical narrative that should be recommended for anyone interested in learning more about Champagne and its unparalleled uniqueness!

You might also like:

|

|

|