By Joseph Temple

From those of us who simply slice it into our breakfast cereal to the diehards who consider it to be an integral part of their post exercise smoothie, the banana is ubiquitous in every city across the United States. Whether it’s the need for potassium, fiber or affordable flavor, Americans have made them the highest selling fruit crop for over a century. And despite the thousands of miles they have to travel in order to get here, bananas continue to outsell apples at the grocery store, even though the latter is usually grown within mere miles of many U.S. cities.

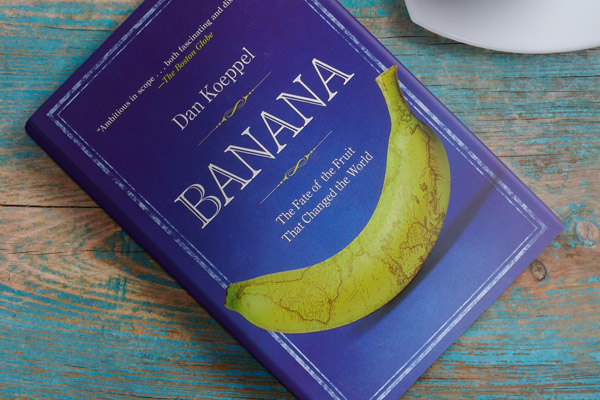

But behind this spectacular rise is also a dark past—and a murky future. With the banana’s friendly price tag came numerous coup d’états and military juntas that completely altered the political landscape of numerous countries near the equator. Meanwhile, with the possibility of crippling diseases making their way across the oceans, many are uncertain that this cherished fruit can survive into the next century. It is a fascinating subject that author Dan Koeppel dives into with his 2007 book Banana: The Fate of the Fruit That Changed the World. “The banana is one of the most intriguing organisms on earth,” writes Koeppel. “Most of us eat just a single kind of banana, a variety called Cavendish, but over one thousand types of banana are found worldwide.”

If you’ve eaten plenty of bananas over the course of your life, then you’ll definitely have a new appreciation for this fruit by learning just how important they are across the globe. For example, in Uganda, a country that grows 11 million tons annually (or 500 pounds per person), famine and hunger is nearly nonexistent due to its banana production. Likewise, to combat Vitamin A deficiencies that affect 150 million children worldwide, the Federated States of Micronesia may have the answer in a hybrid known as Utin lap, which contains 6,000 micrograms—far more than the daily requirement for a child—of beta-carotene, a precursor to Vitamin A.

Another fascinating chapter deals with the continent of Asia, and more specifically, India. As the author points out, “If banana consumers were as enthusiastic and inquisitive as wine lovers, a tour of Asia’s groceries and plantations would be the equivalent to a visit to Bordeaux or the Napa Valley.” Of course, nowhere are people crazier about this fruit than in India, which grows approximately 20 percent of the world’s bananas and has more varieties than anywhere else. While many will scoff at the Indian practice of substituting tomatoes for bananas in their ketchup, you can’t help but feel shortchanged at the grocery store when you learn that there are so many different types beyond Cavendish (the ‘McDonalds of bananas’ according to the author) that we in North America have become so accustomed to. After finishing Koeppel’s book, the urge to try something new will make you go bananas!

Chiquita Banana commercial from the 1940s

For history buffs, a large section is rightfully dedicated to the disturbing role that bananas have played in the Americas since the late nineteenth century. Beginning in 1870 with Captain Lorenzo Dow Baker who made the first commercial transaction by bringing back 160 bunches of Gros Michel to the United States from Jamaica, we learn all about the banana craze that eventually made it America’s number one fruit. Interestingly, at first, the banana was considered a luxury item and extremely taboo due to its phallic nature, requiring an aggressive marketing campaign to assure women of the Victorian Era that it was perfectly fine to eat. But as the twentieth century began, the cost of bananas came down significantly due to several factors. The first was its monoculture where companies focused exclusively on growing only the Gros Michel or “Big Mike” cultivar. Unlike apples, which have many varieties resulting in higher prices, bananas were kept simple, allowing them to undercut their competition despite the distance they had to travel in order to reach consumers. More importantly however was that in order to keep costs down, wages needed to be low, yields high, and countries completely subservient to their interests.

From 1900 to 1930, approximately 25 interventions were conducted by the United States military on behalf of the banana companies, helping them overthrow governments and squash uprisings. In fact, we learn that the term “banana republic” was popularized in a story for Esquire magazine in 1935, describing countries that bent over backwards in order to accommodate the U.S. government and its fruit companies. United Fruit (now Chiquita), the company synonymous with this era is highlighted in great detail, especially for its role in CIA-backed overthrow of President Jacobo Árbenz in 1954.

However, as Koeppel contends, all of these incursions ended up being pyrrhic victories for United Fruit. Following the numerous regime changes, a new threat emerged that couldn’t be bribed or overthrown: Panama disease. A fungus that knows no boundaries, the damage this disease did to United Fruit’s banana fields was so extensive that by 1960, the Gros Michel that millions of people had grown up eating was nearly gone. But instead of finding ways to combat it, United Fruit simply tried to find more land while its competitor Standard Fruit (now Dole) began growing Cavendish, a banana resistant to Panama disease. This strategy would end up knocking United Fruit off its pedestal as the number one banana grower.

More than fifty years later, the question that still remains is could another plague reach the Americas? Koeppel certainly believes so, stressing other diseases like Bunchy Top and Black Sigatoka while demonstrating how easy soil can be contaminated. All it takes is one person with traces of it on their shoes to destroy entire banana fields. And since the business model of American banana growers is based on a monoculture, this makes them particularly vulnerable. Oenophiles will undoubtedly draw parallels between this scenario and the phylloxera epidemic that nearly destroyed France’s vineyards in the nineteenth century. So, could cross breeding bananas work the same way grafting vines on resistant rootstock worked for vintners?

A key strength of the book comes from the tangible solutions that the author proposes. In addition to advocating cross breeding, Koeppel also recommends genetic engineering, a proposal that won’t win him any friends with the organic crowd. Also, it is time for consumers to demand a greater selection of bananas, moving beyond the standard Cavendish. After all, many think that it pales in comparison in terms of taste with the other varieties. And since it seems inevitable that an epidemic will hit Central and South America, it is time that consumers take action before the banana is gone forever.

You might also like:

|

|

|