By Joseph Temple

It looks like one man’s Madeira is now America’s liquid treasure!

While going through a six-month renovation project, Liberty Hall, a National Historic Landmark located on the campus of Kean University garnered headlines this week as it became the site of a great archaeological discovery. Originally built in the 1770s for Thomas Livingston, one of the founding fathers and New Jersey’s first governor, many important Americans have stayed there, including George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, and John Adams. But in addition to all its famous residents and guests, Liberty Hall can now add to its rich history by having the distinction of housing the oldest collection of Madeira in the United States.

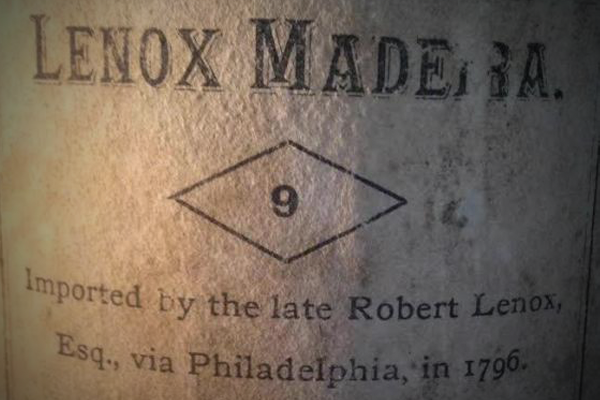

After dismantling a wall inside the wine cellar constructed during the Prohibition era, architects uncovered 50 bottles and 42 demijohns of rare fortified wine that is almost as old as the country itself. With some Madeira bottles dating back to 1796, Bill Schroh, a director at the Liberty Hall Museum, told ABC News that “we never could have imagined finding what we did.” According to their research, the bottles were imported by Robert Lenox, a major player in the New York city wine trade and the estimated value of each bottle could be in the neighborhood of $20,000. Tracing back the origins of their purchase, it is believed that they were imported in order to celebrate the inauguration of John Adams, America’s second president.

Considering that Madeira is no longer a fashionable drink in America, at first glance, it might seem like a strange choice. But during the revolutionary era, having a glass of this fortified Portuguese wine embodied the spirit of the Gadsden flag and its iconic message: DONT TREAD ON ME. Since the archipelago of Madeira was technically in Africa, its wines weren’t subject to harsh taxation like other European imports nor were they required to sail on British ships, making Madeira a symbol of what taxation with representation might look like. Historian John Hailman writes, “By the late eighteenth century it was considered patriotic to drink Madeira and thereby avoid taxes to the Crown, and Madeira thus became the veritable mother’s milk of the American Revolution.”

An added bonus was that unlike Bordeaux or Burgundy, Madeira was virtually indestructible. In fact, seamen quickly discovered that the intense heat and humidity on board the ships transporting it to the thirteen colonies actually made the wine improve—a fact that made it wildly popular in the South. So during the Revolutionary War and following America’s independence, Madeira was consumed by many future presidents, including George Washington and Thomas Jefferson.

Of course, John Adams was no exception. Back in 1768, when John Hancock tried to smuggle a cargo of Madeira into the Boston Harbor and was intercepted and charged by the British, he was represented by none other than the future commander-in-chief. Growing fond of this particular drink, which he enjoyed quite regularly, he once said that “a few glasses of Madeira made anyone feel capable of being president.”

And by ordering Madeira to celebrate his election victory, the people at Liberty Hall couldn’t have purchased a more symbolic wine—the wine of the revolution!

Sources:

Dubourcq, Hilaire. Benjamin Franklin Book of Recipes. London: Fly Fizzi Publishing, 2004.

Hailman, John R. Thomas Jefferson on Wine. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2009.

You might also like:

|

|

|

I first started collecting Madeira when The Rare Wine Company in Sonoma, California, began representing families of wealthy Madeira lovers who purchased vast quantities of aging madeira in barrels and casks from the production companies who began to go out of the business due to better economic use of the land and to the the lack of world-wide demand in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. Rare Wine Company offered these families a marketing opportunity to bottle and sell this great old madeira, turning their investment into cash. Rare Wine cornered hundreds of barrels of 50 to 100 year old madeira from dozens of the these families, and began educating and selling their vast customer mail-list base on the quality of Madeira wine. This was a “win-win-win” for 1. the families that had been holding on to the madeira, 2. for Rare Wine Company, and 3. for the wine customers who now had a market place to buy these fantastic wines.

As far as I have ever heard, no one has ever opened a bottle of Madeira that was “over the hill.” They just keep getting better and better. By the way, most of the older (prior to the 1900’s) madeiras were soleras, so the date (if any) on the bottle was just indication of the first vintage of the solera. I have come to think of madeira as the best dessert wine in the world.