In preparation for Richard Nixon’s groundbreaking trip to the People’s Republic of China in 1972, an enormous amount of classified material was created for the U.S. diplomatic team traveling with the president. National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger briefed Nixon extensively during the months leading up to the visit, going over every detail in this high stakes game of diplomatic chess with Premier Chou En-lai. And while the biggest issues during these talks would be over Taiwan and Indochina, in retrospect, the most important briefings the president and his team received were the ones regarding the food they were about to eat.

“The Chinese take great pride in their food,” declared one memo. Another recommended that Nixon stroke their egos at the dinner table as “they react with much pleasure to compliments about the truly remarkable variety of tastes, textures and aromas in Chinese cuisine.” In terms of what to expect, nothing was left off the table. Although Kissinger and Alexander Haig had been served delicious Peking duck in their preliminary meetings with the Communist Chinese, anything from shark fins to bird’s nests could appear on the president’s plate.

Knowing that the trip would either make or break him, Nixon left nothing to chance. Always one to brush up on an important subject, the president carefully studied the Chinese and their customs. “You should not be offended at the noisy downing of soups, or even at burping after a meal,” one document warned. For months, he, his wife Pat and Dr. Kissinger all took lessons on how to properly use chopsticks, even practicing on the flight over. Of course, all this preparation was not just for his gracious hosts but for the American people watching on their television sets back home.

A document prepared for the Nixon team advising them to compliment their hosts.

Scheduling this visit during an election year was a risky move to say the least. In the suburbs of middle America, the patriotic anti-Communist “Silent Majority” that Nixon needed to secure his re-election was apprehensive about easing relations with the Chinese – the same Chinese that the United States battled just twenty years earlier on the Korean Peninsula. And with all of the official discussions being held in strict secrecy, Americans needed a visual aid to act as their own diplomatic barometer.

Of course, Richard Nixon made sure they got one.

Realizing the enormous power of a photo-op, the administration stressed the superficial aspects of the visit. It was no coincidence that Air Force One landed at the Capital Airport at 11:32 A.M. Beijing time. Across the United States, it was prime time when the president and Chou shook hands, giving millions of Americans the chance to watch this symbolic act live via satellite. It also wasn’t a coincidence that of the one hundred journalists accompanying the commander-in-chief to China, those in television were given preference over their colleagues in print. While personally despising most of the media, the president also knew that a carefully controlled press parroting the administration’s narrative through stunning visuals could sway public opinion over to Nixon.

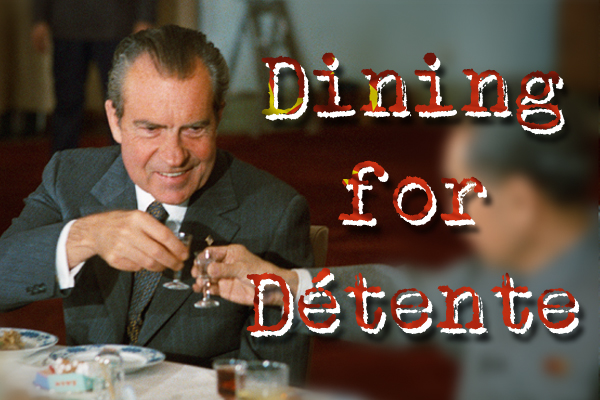

For the next stunning a visual, an extravagant banquet had been prepared for nearly six hundred guests at the Great Hall of the People. With giant American and PRC flags towering over the captivated audience, a series of congratulatory toasts were made by Nixon and Chou to usher in a new era of understanding. It was here where food and drink played perhaps the most important role in convincing the American people that Nixon had pulled off the greatest foreign policy coup in a lifetime.

A video prepared for the U.S. diplomatic team

outlining the differences in the American and Chinese diets.

For beverages, each guest at the banquet was given three glasses: one for orange juice, one for wine and one for a Chinese drink with over 50% alcohol known as Maotai. Worried that this intoxicating spirit would take its toll on a president who needed to be flawless throughout the entire evening, Deputy Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs Alexander Haig cabled the White House in January to warn them of this drink. In the book Nixon in China: The Week that Changed the World, historian Margaret MacMillan writes that Haig stressed “UNDER NO REPEAT NO CIRCUMSTANCES SHOULD THE PRESIDENT ACTUALLY DRINK FORM HIS GLASS IN RESPONSE TO BANQUET TOASTS.” Nixon, seeking a middle ground did drink form his glass but in very small sips.

Next came the food that each guest would enjoy with his/her own personally inscribed chopsticks. On the menu were dumplings, fried rice, three colored eggs, shark fins, and duck slices garnished with pineapples, among others. Eating next to Chou En-lai, Nixon fared much better with chopsticks than CBS anchorman Walter Kronkite who accidentally shot an olive at a neighboring table. Careful not to lay it on too thick, the president was warned “not to say a particular dish is ‘good’ or ‘interesting’ when in fact you do not like it, as your hosts, in an effort to please, may serve you extra portions to your embarrassment.”

Covered for four hours straight without commentary by the big three U.S. networks, the entire banquet proved to be the ultimate combination of dining and diplomacy. Nixon, the once ardent anti-Communist ironically quoted Chairman Mao by asking both countries to “Seize the Day. Seize the hour.” And as the two sides clinked their glasses in friendship, the Chinese Red Army band performed a rendition of both “America the Beautiful” and the U.S. National Anthem to an audience of millions watching live on TV. This in addition to a close-up shot of the president using chopsticks had undoubtedly convinced a majority of Americans that the visit was a rousing success. Despite being just the first night of a seven-day trip, the symbolic image of two former adversaries breaking bread proved to be more powerful than any treaty, agreement, or communiqué signed later on.

Writing in his diary the next day, H.R. Haldeman, the president’s trusted chief-of-staff was more than pleased with how the media presented the entire evening. “The network coverage … of the banquet period was apparently very impressive and they got all the facts the P (President Nixon) wanted, such as his use of chopsticks, his toasts, Chou’s toast, the P’s glass-clinking,” wrote Haldeman. According to Nixon biographer Conrad Black, his trip had registered the highest U.S. public recognition of any event in the history of the Gallup poll. And in the days and months after Nixon’s visit, Chinese restaurants in the U.S. were mobbed by foodies seeking out “authentic” Chinese cuisine like the Peking duck they saw the president eating on TV, writes Andrew Coe, author of Chop Suey: A Cultural History of Chinese Food in the United States.

Call it “chopstick diplomacy,” “Maotai statecraft” or “dining for Détente,” but in the end, Richard Nixon had proved that the power of food could win over the public at large as he tore down the Bamboo Curtain.