By Joseph Temple

Just mention the word Cristal and most of us think of Hollywood celebrities and hip-hop moguls spending frivolously on expensive bottle service while partying late into the night. Beginning in the 1990s, this brand of Champagne has been referenced in so many rap songs that it is now synonymous with a culture defined mostly by escapism and braggadocio. And although there has been a falling out between its makers and the hip-hop community over recent years, it’s easy to see how this particular bottle of bubbly, distinctly wrapped in cellophane, came to symbolize the desire for luxury and wealth. After all, its original purpose was appealing to the vanity of a Russian tsar.

Searching for the origins of Cristal, one has to travel back in time to when Russia was one of the most highly sought-after markets for the great Champagne houses. As a result of the Napoleonic Wars where Russian soldiers briefly occupied the region, stories about the quality of its bubbles were sent back to the royal family, and very quickly, fizz became one of France’s most favored exports. Describing the breakthrough success of Veuve Clicquot during this time period, author Tilar J. Mazzeo writes, “Those same aristocratic officers who had come to love her wine during the occupation of Reims were now prepared to buy her champagne at any price. Soon, Czar Alexander declared that he would drink nothing else. Everywhere one heard the name of the Widow Clicquot and praises for her divine champagne.”

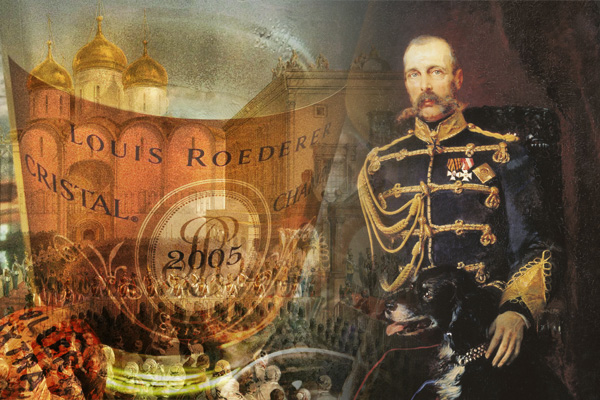

Enter the house of Louis Roderer and its most famous customer, Tsar Alexander II, a well known oenophile, and what you have are the makings of perhaps the most unique bottle of champagne in history. While Cristal today is known for its dry and clear taste, back in 1876, when the son of Louis Roderer created a prestige cuvée specifically for Russian royalty, it needed to appeal to the tsar’s well-known sweet tooth. Adding 20 percent of sweet liqueur and a collop of yellow Chartreuse to the pinot noir and chardonnay, Roderer succeeded in developing a wine that became the toast of the royal court. However, the drink was only one element—the other became its distinct packaging.

Not wanting to be seen drinking the same bubbly as the rest of the riff-raff, the tsar demanded an exclusive product that would stand out and one that only he could drink. The result became its iconic see-through design, which separated itself from the green bottles that everyone else drank from. The only difference from today is that back then, Cristal bottles were actually made from lead crystal.

Next came the flat bottom, designed specifically without a a punt. Having survived several assassination attempts, the tsar rightfully feared that his potential killer might sneak a bomb underneath a wine bottle, causing Roderer to make an adjustment that is still with us today. Of course, in the end, this design did not prevent the tsar’s murder in 1881. Even more devastating for Roderer was the Russian Revolution, which disposed his son Nicholas II from power. With this pivotal event, Cristal lost approximately 75% of its market overnight.

It would not be until 1945 that the general public finally got to taste this champagne, which is now wrapped in orange cellophane to protect against sunlight. But ever since its grand debut in 1876, Cristal has gone on to be one the most famous and recognized brands in the world, consumed by tsars, kings and celebrities alike.

Sources:

Clarke, Oz. The History of Wine in 100 Bottles: From Bacchus to Bordeaux and Beyond. London: Pavilion Books, 2015.

Hammond, Carolyn. 1000 Best Wine Secrets. Naperville: Sourcebooks, Inc., 2006.

MacLean, Natalie. Red, White, and Drunk All Over: A Wine Soaked Journey from Grape to Glass. London: A&C Black, 2010.

MacNeil, Karen. The Wine Bible. New York: Workman Publishing, 2015.

You might also like:

|

|

|