Photo by Alain Elorza [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

By Joseph Temple

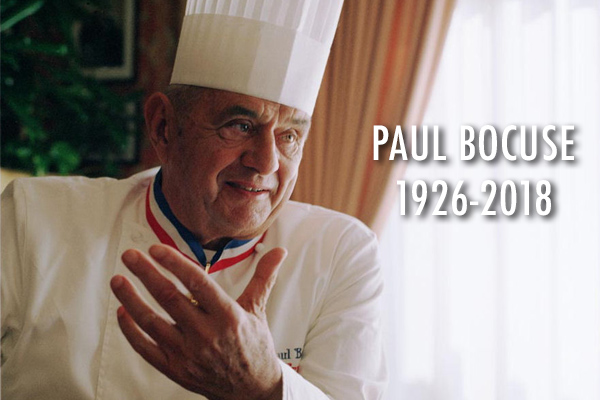

This year, on the 20th of January, the culinary arts lost one of its most prolific chefs when Paul Bocuse passed away at the age of 91 as a result of Parkinson’s disease. A charter member of the New Wave of French Cuisine, Bocuse’s footprints were long-lasting and are still seen today in restaurants across the world. Stressing fresh ingredients combined with lighter and purer sauces, his revolutionary approach represented a stark contrast—and a departure from the methods of Auguste Escoffier and haute cuisine.

Born in 1921, Bocuse was raised in Collonges-au-Mont-d’Or, located in the metropolis of Lyon in eastern France. Tracing his gastronomic roots back seven generations to 1765 when Michel Bocuse, a local boatmen operated a fried fish shop on the bank of the Saone, the young chef-to-be spent his formative years catching frogs and foraging for strawberries in the nearby woods. As a 16-year old student of chef Eugénie Brazier, Bocuse would go on to cut his teeth in Vienne as the protégé of Fernand Point at the legendary La Pyramide restaurant. After opening his own establishment, L’Auberge du Pont de Collonges in 1952, a new and dramatic approach was about to be created in his kitchen.

Described by some as a French chef straight out of central casting who was known to be quite intimidating, he received his first Michelin star in 1958 and a second one in 1960. But during this wilderness period, Bocuse often reflected on the trials and tribulations that eventually led to stardom. Claiming that his restaurants usually lost money and had to be bailed out by the profits from his catering businesses, he once said, “Some men have mistresses. I run a luxury restaurant.” But as the 1960s progressed, Bocuse and the other rule breakers suddenly found themselves on the ground level of something very special.

To truly understand the legacy of Bocuse, we have to look at the culinary arts before he and the other Young Turks in France embarked on their revolutionary approach to fine dining. As part of the Escoffier system, heavy sauces were often used to mask the raw ingredients, which tended to spoil under antiquated storage conditions. Although delicious and world renowned, the traditional style was often heavy and rich in calories. So in reaction to this dated approach, Bocuse and others created what came to be known as nouvelle cuisine (although some Bocuse biographers have noted that he had no idea what the often nebulous term actually meant; others insist that he was never part of the movement at all, but rather just a very good classical chef).

By Arnaud 25 (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

In a nutshell, the general concept behind nouvelle cuisine was simpler and less spectacular fare. Avoiding flour as a binding agent, certain edicts included “Reject unnecessarily complex preparations” and “Reduce cooking times.” Gone were the expensive and thick sauces synonymous with Escoffier, which were substituted with simplicity. Even more revolutionary for the time was Bocuse personally seeking out the freshest ingredients. One article written by a Canadian journalist who traveled to Lyons in 1965 stated: “At dawn, he hops into his blue Renault van and drives five miles to an open air market to find organically grown vegetables and fresh fish.”

The movement became known for lighter meals that were friendlier to people’s waist lines. Julia Child famously noted that chefs had “finally gotten it through their thick heads that there are some people who don’t want to be stuffed full of fat and truffles.” But the truth is more nuanced. For example, one Bocuse meal included truffle soup (his specialty), salmon with sorrel sauce, duck cooked in Bordeaux wine, and a liqueur-drenched cake topped with shaved chocolate—not exactly the type of meal for one looking to lose weight. As author David Kamp states, “The nouvelle-ists were not against calories or decadence per se … but against a French cuisine they felt had grown leaden, gloopy and uninspired.”

Luckily for Bocuse, his new wave approach found a receptive audience as it mirrored what was going on in French society-at-large. In an atmosphere of student strikes and labor unrest, a new foodie publication, Le nouveau guide—a Cahiers du cinema published as its first headline: MICHELIN: DON’T FORGET THESE 48 STARS! Opining that the authoritative Michelin Guide, which could make or break any restaurant in the Fifth Republic, had been far too Escoffier-centric in how it awarded its stars, the publication suggested checking out this new Gastronomic Mafia.

The results were startling! Although Bocuse’s restaurant had been awarded Michelin’s highly coveted third star in 1965, seven years later, the world famous red book gave stars to eight fewer restaurants specializing in haute cuisine than it did in the previous year. The change had been so dramatic that by 1975, French President Valery Giscard d’Estang awarded Bocuse with the prestigious Legion of Honor. “France has this great advantage,” said Bocuse on a visit to Toronto that same year. “Every day we talk about what we ate the night before. Then we worry about what we are going to eat this evening.”

Perusing through the 1965 Michelin Guide, it informs us that for eight dollars, you are expected to enjoy one of the best meals in the world at L’Auberge—paired with a Morgon burgundy wine of course! A specialty for many years was Loup en croute farci mousse homard, which translated to a big fish stuffed with lobster mousse and then fitted into a pastry crust. But others including actress Bridgette Bardot, who was known to dine regularly at Bocuse, enjoyed a saddle of lamb roasted with the herbs of Provence.

Even more trailblazing was Bocuse’s decision to step from outside his kitchen and into the spotlight in order to promote what became a truly global brand. Spearheading what became “the celebrity chef”, Bocuse reveled in the spotlight, telling one newspaper: “You’ve got to beat the drum in life. God is already famous, but that doesn’t stop the priest from ringing the church bells every morning.” Appearing on the cover of Time magazine, the windfall of publicity helped him launch his very own line of frozen foods as well as numerous restaurants, located everywhere from Tokyo to Epcot Center in Florida. Expanding his empire, by 1974, Paul Bocuse Incorporated earned an estimated $4 million dollars in wine sales alone, while Air France hired him as an advisor for in-flight cuisine. Symbolizing his worldwide impact, he launched the Bocuse d’Or competition in 1987 where teams representing different countries squared off in what became known as the Olympics of food. Reveling in the limelight as the ultimate hybrid of chef and entertainer, Christian Millau once told him “Paul, I’m afraid you missed your calling in life.”

According to author Michael Steinberger, “He [Bocuse] demonstrated that not only could chefs escape the grimy, grinding business of making food; they could become wealthy and famous in the process. They could act and be paid like captains of industry and treated like rock stars. For men who had spent decades hunched over hot stoves, often at great cost to their health and happiness, this was an enticing prospect.”

Inspiring a host of chefs who have gone on to launch their own culinary empires, Bocuse stands out as a pioneer in this field. And his impact on the gastronomic arts is undeniable as numerous restaurants still employ the guiding principles of nouvelle cuisine to this day. For his enormous contributions, the International Wine and Food Society salutes Paul Bocuse as one of the great chefs of the twentieth century!

Sources:

Kamp, David. The United States of Arugula: How We Became a Gourmet Nation. New York: Broadway Books, 2006.

Steinberger, Michael. Au Revoir to All That: Food, Wine, and the Decline of France. New York: Doubleday, 2010.

You might also like:

|

|

|