By Joseph Temple

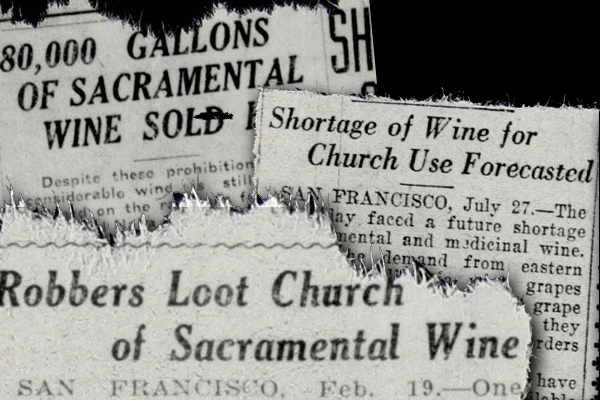

In last week’s blog entry, we traveled back in time to the era of Prohibition, looking at the rise of Alicante Bouschet, a grape that experienced a tremendous boom due to a clause in the Volstead Act. Allowing citizens to make “non-intoxicating” fruit juice and ciders for “home use,” this legal loophole led to an explosion in amateur winemaking, causing consumption to go from 60 million gallons annually in 1919 to 150 million gallons. But just as important was another loophole that kept a few lucky wineries alive during the “noble experiment” – a loophole that allowed wine to produced and sold for sacramental purposes.

And taking immediate advantage of this clause was Georges de Latour, owner of Beaulieu Vineyard in the Napa Valley who moved quickly to acquire a license to produce sacramental wine. So during this thirteen-year period which saw the number of wineries nosedive from around 700 in 1919 to just 130 before repeal in 1933, Beaulieu Vineyard actually thrived by cornering the market on sacramental wine.

Arriving in the United States in 1883, de Latour, a wealthy French chemist who made his fortune by developing tartaric acid would buy four acres of land in Napa—land that consisted of wheat fields and orchards until his arrival. Incorporating it into Beaulieu Vineyard in 1904, the land became known for its Cabernet Sauvignon as one of Napa’s 120 wineries. However, unlike most of his competition, de Latour adapted to the new reality as National Prohibition took effect on January 16, 1920.

Described as “one of the best known families in San Francisco” by one newspaper, the de Latour’s used their connections in the Catholic community to become “The House of Altar Wine.” After receiving his license to make sacramental wine in March of 1920, de Latour received what historian Daniel Okrent described as “the key to a fortune” by winning approval of the Archbishop of San Francisco to supply altar wines. Of course, having two Catholic priests on the first board of directors for Beaulieu Vineyard played a huge role in getting this business—especially since one had a direct connection to the archbishop.

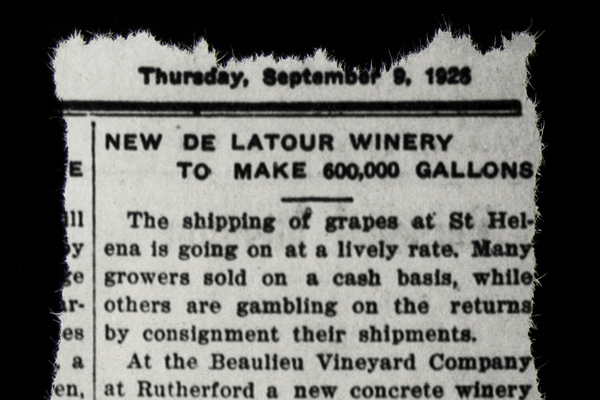

Soon thereafter, de Latour piled up endorsements from other religious figures across the country as the go-to source for sacramental wine. With an office in New York City, Beaulieu Vineyard had key distributors in seven eastern and Midwestern cities by 1922, resulting in the construction of a brand new facility four years later to produce a vintage in the neighborhood of 600,000 gallons. As Okrent explains, schmoozing the clergy played an important role in building his business: “de Latour’s most brilliant marketing gesture was the construction of a guest cottage for visiting clerics and a standing invitation to any who wished to visit Beaulieu and the test the wines on the spot.”

Producing sacramental wine until 1978, this market allowed Beaulieu Vineyard to survive Prohibition as hundreds of vineyards fell by the wayside. “The House of Altar Wine” as Beaulieu was described had survived in tact, earning dividends that today would be worth more than a million dollars!

Sources:

Clarke, Oz. The History of Wine in 100 Bottles: From Bacchus to Bordeaux and Beyond. London: Pavilion Books, 2015.

Okrent, Daniel. Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition. New York: Scribner, 2011.

Taber, George. Judgement of Paris: California vs. France and the historic 1976 Paris tasting that revolutionized wine. New York: Scribner, 2005.

Weber, Lin. Prohibition in the Napa Valley: Castles Under Siege. Mount Pleasant: Arcadia Publishing, 2013.

California Digital Newspaper Collection

You might also like:

|

|

|