By Joseph Temple

Today Alicante Bouschet, a French hybrid originally designed to darken up poorly colored red wines is nearing extinction. In the United States, this teinturier grape is grown mostly in California’s Central Valley as an extender in jug wines. Pulpy and sugary, novelist Idwal Jones declared it to be so deplorable that “it ranks somewhat below the gooseberry” while wine critic Frank Schoonmaker said it had “no place in any respectable vineyard and should be eliminated.”

And yet despite all its numerous flaws, would you believe that Alicante Bouschet was at one time the most popular wine grape in America???

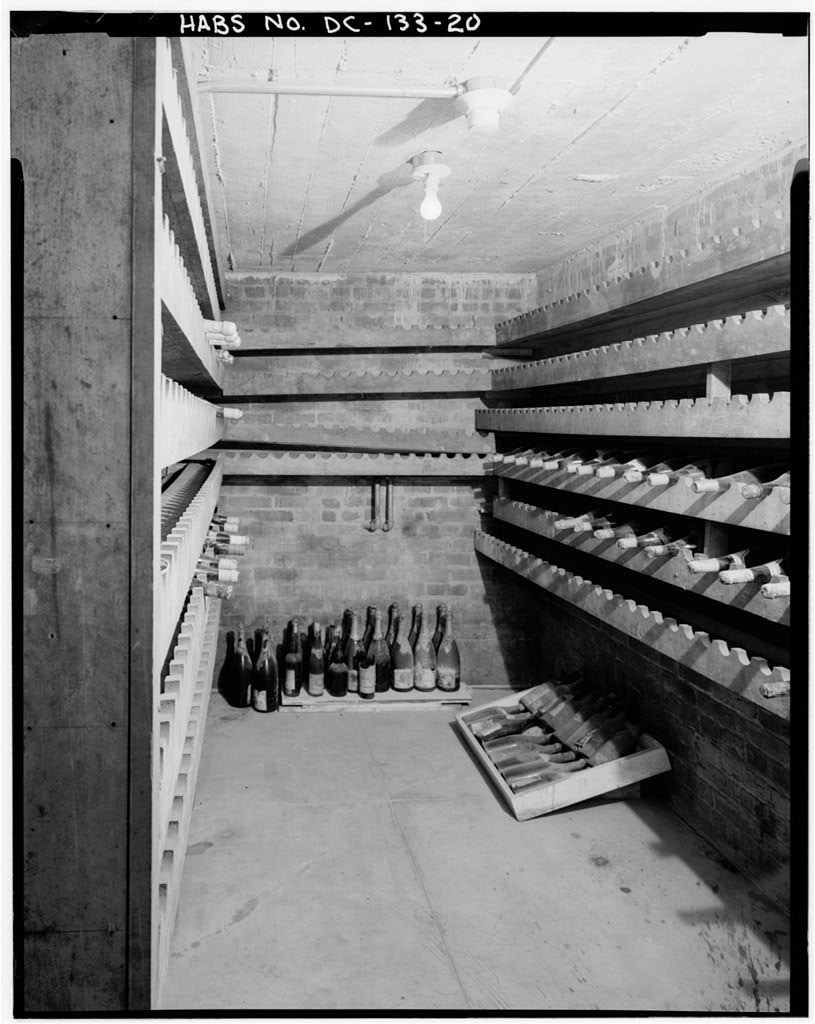

To understand how it became so popular, one needs to travel back in time nearly a century ago to the age of Prohibition. With passage of the Volstead Act in 1919, the production, sale and transport of intoxicating liquors became the law of the land. However, there was an important loophole that thousands of citizens gladly took advantage of. Besides never properly defining what constituted “intoxicating liquors,” the act allowed individuals to produce “non-intoxicating cider and fruit juices exclusively for use in his home.” With this legal ambiguity, amateur winemakers sprouted up all across the United States seemingly overnight. What they needed were some grapes to ferment.

Although Zinfandel was the largest grape in California in terms of vineyard acreage, its skin couldn’t withstand the long and bumpy freight train ride to the lucrative east-coast markets of New York, Boston and Philadelphia for home use. On the other hand, Alicante Bouschet, a Vitis vinifera grape first conceived in southern France during the 1860s by crossing Grenache and Petit Bouschet had a hard and thick skin that easily made it across the country. Of course, this important selling point played a big role in causing vineyard land in the Golden State to jump from $100 an acre in 1919 to $500 a year later as home winemaking shot up by 50 percent during Prohibition.

Another key advantage was the abnormal amount of juice contained in Alicante Bouschet. Unlike other grapes, you could press Alicante two and sometimes three times to yield twice the amount of fermentable juice. And notwithstanding its bland and leathery taste, the red flesh added much needed color to unskillful and shoddy winemakers working on their latest vintage. According to historian Daniel Okrent in his book Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition, “On the standard scale used to measure color in grapes, anything that scored over 150 had ‘more than three times the color usually necessary for wine or juice.’ Zinfandel scored a pale 38, cabernet sauvignon a respectable 86. Alicante weighed in at a bruising 204.” All of a sudden, thin and watery wines made in someone’s basement had the appearance of a standard red.

From 18,000 acres of Alicante Bouschet plantings in 1919, that figure grew to 39,000 acres by 1932 as a growing frenzy took hold—right up until the repeal of Prohibition. With decent grapes being made by professional winemakers again, Alicante was relegated to the dustbin of history; by 1997 a mere 1,600 acres in the Central Valley were dedicated to this grape. Prohibition’s great grape had run its course, being remembered as a grape that gave many thirsty Americans of the 1920s a wine that they probably care not to remember.

Sources:

Acitelli, Tom. American Wine: A Coming-of-Age Story. Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2015.

MacNeil, Karen. The Wine Bible. New York: Workman Publishing Company, 2000.

Okrent, Daniel. Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition. New York: Scribner, 2011.

Pinney, Thomas. A History of Wine in America from the Beginnings to Prohibition. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989.

Sosnowski, Vivienne. When the Rivers Ran Red: An Amazing Story of Courage and Triumph in America’s Wine Country. Basingstroke: Macmillan, 2009.

You might also like:

|

|

|