By Joseph Temple

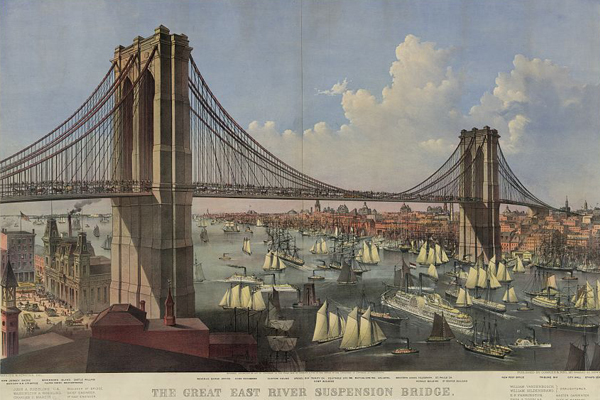

When a colossal steel-wire suspension bridge connecting the boroughs of Manhattan and Brooklyn (described as the “Eighth Wonder of the World”) debuted in the spring of 1883, the future of New York changed forever. Known today as the Brooklyn Bridge, its two massive towers dominated the city skyline, and for years remained the tallest structure in the Western hemisphere. However, the real value lay in its practicality as originally envisioned by its designers, John and Washington Roebling. Historian David McCullough, in explaining the massive benefits of the bridge, writes, “Manufacturers would have closer ties to the markets … The mail would move faster … Most appealing of all for the Brooklyn people who went to New York to earn a living every day was the prospect of a safe, reliable alternative to the East River ferries.”

But beyond the obvious advantages of a structure that is crossed by 120,000 vehicles and 4,000 pedestrians nearly every single day is another benefit unknown to many: the Brooklyn Bridge also served as a massive wine cellar.

Reported earlier this year by National Public Radio, wine storage became an offshoot for the bridge’s designers due to several reasons. The first was economical; with a massive price tag of $15 million dollars (more than $300 million today) to build the bridge, the Roeblings needed to find other sources of revenue to allay the growing costs. Secondly, when construction began, two merchants on opposite sides of the East River, Rackey’s Wine Company and Luyties & Co. were suddenly uprooted. Therefore, what better way to bring them—as well as other businesses—back into the fold by carving out vaults underneath the ramps leading up to the giant anchorages? Most importantly, because the vault’s temperature barely changed throughout the course of the year, it became the perfect spot for storing wine.

Open for business seven years before the Brooklyn Bridge debuted on May 24, 1883, the cellars today are no longer used to house the finest Bordeaux, Burgundy and Champagne. Sadly inaccessible to the general public for security reasons, what we know about them is sure to impress. On the Manhattan side, a statue of the Virgin Mary stands at the entrance way along with Old World frescoes and the phrase, “Who Loveth Not Wine, Women, and Song, He Remaineth a Fool His Whole Long Life.”

According to Nicole Jankowski of NPR, over time the walls were painted with designs of provincial Europe along with street names such as Avenue Les Deux Oefs and Avenue Des Chateaux Haut Brion. One author in a book published in 1894 writes, “Years of time and a small fortune in money have been spent in fitting up these vaults for their purpose, and they now constitute a magnificent wine-cellar, perhaps equal to the finest to be found in Europe.”

With the start of the Second World War, the cellars were closed down permanently, with only a few select government employees having access to a site rich in historical artifacts. But as more people become aware of this hidden history, perhaps New York can initiate a new form of wine tourism? After all, the suspension is killing us!

Sources:

Greenberg, Stanley. Invisible New York: The Hidden Infrastructure of the City. Baltimore: JHU Press, 1998.

Hymowitz, Kay S. The New Brooklyn: What It Takes to Bring a City Back. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017.

McCullough, David. The Great Bridge: The Epic Story of the Building of the Brooklyn Bridge. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007.

Morris, Charles. Makers of New York: An Historical Work, Giving Portraits and Sketches of the Most Eminent Citizens of New York. New York: L.R. Hamersly & Company, 1894.

You might also like:

|

|

|