By Joseph Temple

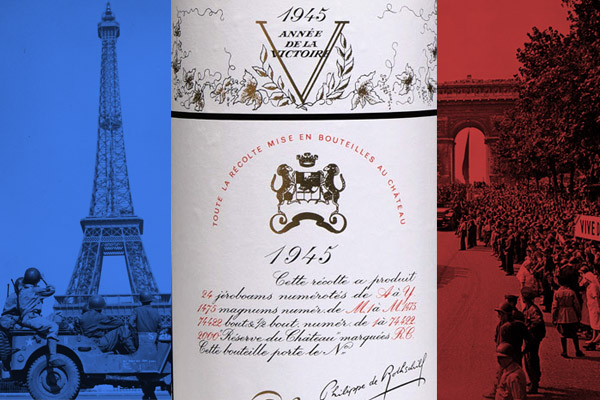

As perhaps the most influential enologist of the twentieth century, the legacy of Dr. Émile Peynaud is with us every time we take a sip of wine. Writing shortly after his death in 2004, Eric Asimov of The New York Times states, “More than any other individual, Dr. Peynaud helped to bring winemakers into the modern world. As a researcher and consultant, he applied rigorous scientific methods to a field bound more often by haphazard custom, guesswork and superstition.”

Born in Bordeaux in 1912, Peynaud’s revolutionary approach to winemaking, exemplified in his two best known books, Knowing and Making Wine and The Taste of Wine, made him highly sought after as a consultant in both his native France and across the world. By changing winemaking from an art to a science, here are just four ways that Peynaud ushered in the modern era that we all enjoy today.

In 2017, it is assumed that estates only pick their grapes when ripe. But before Peynaud arrived, in a good year, it was customary to start picking long before the autumn harvest in order to ensure a sizable crop, no matter how ripe the grapes were. The only time they were left on the vines for a fall picking was during the bad years, explains Oz Clarke in describing the impact of Peynaud. “In the vineyard he [Peynaud] insisted that rotten grapes be discarded—they hadn’t been before—and that growers should relentlessly assess the ripening of the grapes, and only pick when ripe.”

If oenophiles could travel back in a time machine, they would be appalled to see the condition of many wineries throughout France, who usually made their product in vats and barrels immersed in bacteria. The idea of working in a sanitary environment was clearly a foreign concept as Peynaud shockingly discovered while visiting the numerous estates. “Cleanliness is a basic condition for quality. The whole of enological science would be to no avail if the work itself were done in places that were dirty,” wrote Peynaud who strongly advocated for stainless steel vats and new oak barrels as replacements. Given the price tag, it was a change that many fought against, but in the end accepted as a necessary cost in making a superior vintage.

In addition to being spotless, Peynaud also lobbied for temperature controlled tanks to be complimented by cool cellars. Influenced by France’s dairy farmers who could vary the temperature in a stainless steel tank, he demanded that winemakers do the same. Before these two elements became industry staples, unmanageable fermentation and spoilage was commonplace, causing many vintages to turn into vinegar. And since bacteria multiplies faster in warmer conditions, the need for cool cellars with a consistent temperature became a must.

Arguably the greatest contribution of “Peynaudism” is an exact science he perfected known as malolactic fermentation—a secondary fermentation which turns malic acid into soft lactic acid. In layman’s terms, what this does is that it softens the wine, giving red Bordeaux a much smoother taste. In the pre-Peynaud era, winemakers suspected that an additional fermentation was taking place in the vats and bottles, but had no idea how to control it. It was only after Peynaud identified this crucial step (along with all of his other recommendations) that Bordeaux was brought to a whole new level!

You might also like:

|

|

|