By Joseph Temple

When André and Édouard Michelin of France decided to create the Guide Michelin in 1900, no one could imagine that they would be changing the face of gastronomy forever. More than a century after the first edition was given away for free, this world famous book now covers the dining landscape of twenty-three different countries and is considered by many travelers to be the culinary bible. As author Michael Steinberger writes, “In time, it became rare to set foot in a French car that didn’t have a well-worn copy of the famous red book in its glove compartment or side pocket, and in a country in which dining truly was a national pastime, the annual publication of the Guide, with its promotions and demotions, was the Oscars of the eating class.”

Originally designed to sell more Michelin tires by making the brand synonymous with driving and travel, these guide books now have the ability to make or break a restaurant through its powerful three star rating system. Earning just one of these stars can increase a restaurant’s revenue by millions, giving Michelin and their inspectors enormous power over the culinary arts around the world.

And when looking back at the history of the guides, it is chopped full of fascinating stories and plenty of controversy. So have a look below at five unique anecdotes that tell the story of the Michelin Guide—it’s definitely worth a journey!!

1. Origins

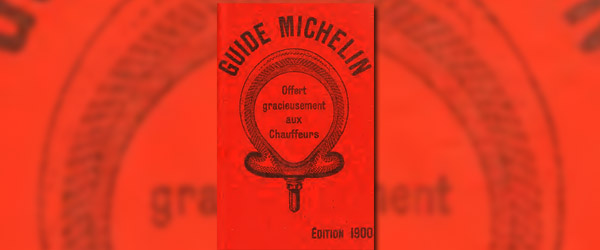

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the whole idea of creating a guidebook for automobile travel was a risky endeavor to say the least. Despite France being the world’s largest market for this new transportation device, the number of individuals who owned one was very small. Considered a niche market for very wealthy people, printing a book containing information about the various hotels and roadways along their route seemed destined for failure.

But as the century progressed, the number of automobiles on the road in France exploded, from just 3,000 in 1900 to over 100,000 by 1914. Taking advantage of this tremendous change, Michelin actively promoted both their products and the guide through clever marketing strategies, which included a cigar-chomping mascot known as Bibendum. As a result, the Guide Michelin quickly became required equipment for all motorists.

2. The Addition of Restaurants

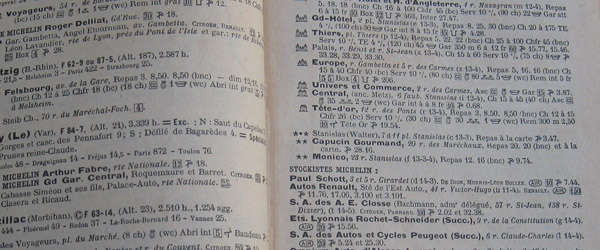

Today, the Michelin Guide is often associated with dining and its renowned star system. So it might come as a surprise to some that it wasn’t until the 1920s that Michelin first began to include restaurants in their guidebook. Never explaining their magic formula for what constitutes a coveted three star rating, the people of France nonetheless trusted them wholeheartedly given the company’s reputation. Soon, chefs realized that just one star was their ticket to fame and fortune, especially for those located in the hundreds of small towns across the French countryside, giving them the opportunity of being placed on the culinary map.

With a stronger focus on dining and less on tires, (the 1900 edition devoted 36 of 399 pages to the subject of tires; in 1927, information about tires constituted just 5 of 990 pages total) sales exploded from a printing of 75,000 guidebooks in 1919 to over a million distributed from 1926 to 1940. And no longer were these books free. After Andre Michelin saw them being used to prop up workbenches at a roadside garage, he decided that people only respect what they pay for and began charging seven francs for the book in 1920.

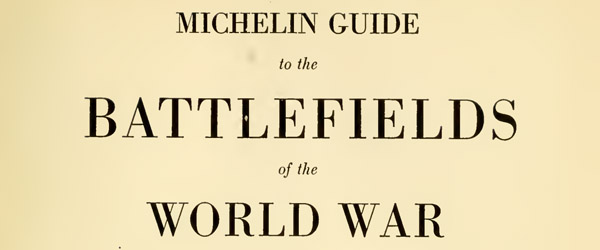

3. A Tool of War

In 1915, as French soldiers were battling the Kaiser’s men in places like Ypres and Champagne, Michelin decided to publish a guidebook to Germany. On the surface, it appeared to be a strange idea, since no motorist was able to freely cross the border. But for Michelin, it was a patriotic exercise designed to boost morale; once they eventually broke through enemy lines, the army would know exactly where to go. Continuing this theme in the post-war period, the company would go on to produce a series of Great War battlefield companions. With such a distinguished reputation, Allied soldiers were given Michelin Guides to help navigate them through liberated France following the invasion of Normandy in 1944.

4. Controversy

In 2004, Michelin faced a PR catastrophe when Pascal Rémy, an inspector of sixteen years published a scathing tell-all book that pulled back the curtain on some of the company’s most guarded secrets. In the book, he alleges that more than a third of restaurants awarded three stars retain their status only because Michelin views them as untouchable. “It is no longer a priority to look for the good small places in the heart of France,” writes Rémy. “The goal is to bring in money. We have to go to the important places, the big-name restaurants, the big groups—that’s what they say at Michelin now.” While Michelin rejects all these claims, the entire episode does cast serious doubt on their rating system, especially with people these days more likely to reach for their mobile device in search of blogs and restaurant review websites.

5. Turning in their stars

The formula for what constitutes a three star rating is a closely guarded secret. As Anthony Bourdain states, “It’s like sausage—no one wants to see how the hell it’s made.” However, many restaurateurs have speculated that décor and not food is what separates two and three stars—a claim that Michelin denies, stating that it is all about what is served on the plate. Requiring millions to upgrade their establishments in order to please inspectors, the result is a more expensive menu, which limits the potential clientele. Additionally, some feel that one must abide by a rigid formula, limiting their creativity in the kitchen. “I know many of the three-star Michelins never change their menu in order to have perfect consistency,” said chef Daniel Boulud. “It’s basically robotic cuisine; they cannot afford to change, because that was the winning formula … Emotionally, I’m going to want to cook something else than what I’ve done.”

Sources:

Clarkson, Janet. Food History Almanac: Over 1,300 Year of World Culinary History, Culture, and Social Influence. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2013.

Harp, Stephen. Marketing Michelin: Advertising and Cultural Identity in Twentieth-Century France. Baltimore: JHU Press, 2001.

Lottman, Herbert. The Michelin Men: Driving an Empire. London: I.B. Tauris, 2003.

Steinberger, Michael. Au Revoir to All That: Food, Wine, and the Decline of France. New York: Doubleday, 2010.

White, Trevor. Kitchen Con: Writing on the Restaurant Racket. New York: Arcade Publishing, 2006.

Zuelow, Eric. A History of Modern Tourism. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan, 2015.

You might also like:

|

|

|