By Joseph Temple

Alongside champagne, nothing has symbolized opulence and luxury more than the consumption of salty little fish eggs, better known as caviar. Long before Robin Leach first appeared on our TV sets, the bourgeois of London, Paris, and Berlin were simply enthralled by this exotic delicacy and the lavishness that surrounded it. When wealthy aristocrats from Central Russia demanded live sturgeon from Astrakhan—sturgeon that had to be transported in large tanks so they could indulge in only the freshest roe—many Europeans eagerly copied their culinary tastes, causing sales of caviar to go through the roof. Arriving first in porous wooden barrels and later in small tins, this scarce product has continued to command extraordinarily high prices. Just nine ounces of Ossetra caviar can cost more than a thousand dollars online.

But over the past twenty-five years, a disturbing trend has wreaked havoc across the Caspian Sea, home to the very best sturgeon. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, a power vacuum led to the dramatic rise of organized crime. With millions of dollars at stake in the lucrative caviar trade, inexperienced poachers, many of them financed by the mafia, began depleting the sturgeon population at a rapid pace. Environmental concerns had been pushed aside in attempting to squeeze every possible fish egg out of the Caspian. Working with corrupt customs officials and seemingly legitimate outfits in Europe and America, chances are that if you purchased Russian caviar in the early 1990s, it most likely passed through the hands of organized crime.

Writing in detail about this stark reality, author Inga Saffron explains why we need to start hitting the panic button in Caviar: The Strange History and Uncertain Future of the World’s Most Coveted Delicacy. Published in 2002, Saffron, a Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist for the Philadelphia Inquirer and the paper’s Moscow correspondent from 1994 to 1998 knows from firsthand experience just how truly dire the situation is. As we see during her research, it seems whatever regulations governments and international bodies put in place to protect the sturgeon, the criminals are always one step ahead of them.

A key problem is that the five countries—Russia, Iran, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan—all share a perimeter around the Caspian Sea. So if the former two decide to crack down on over-fishing, one of the breakaway republics can easily offset it. “Notoriously corrupt, those republics became the center of the underground caviar industry,” writes Saffron. And as the sea became a Wild West for poachers, crude methods that are the antithesis to traditional sturgeon fishing quickly became the norm.

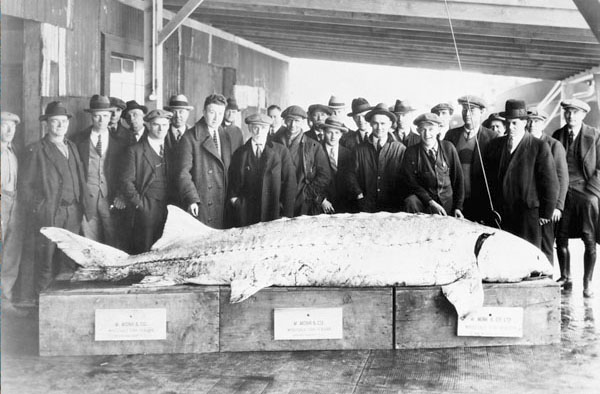

A sturgeon – weight 1020 lbs. – caught in New Westminster, British Columbia.

Image courtesy: Library and Archives Canada

One of the book’s greatest strengths comes from its in-depth look at the history of both the fish and its prized roe. Considered a living fossil by scientists, the sturgeon with their sloping heads and shark-like tails have existed for approximately 250 million years, even before dinosaurs roamed the earth. Consisting of twenty-seven different varieties, some like the beluga, have easily weighed over a ton while a female’s eggs can account for fifteen percent of the bodyweight. Of course, retrieving the eggs at the right age and during the right part of the spawning cycle is paramount. “Sturgeon are in no hurry to reproduce. They take almost as long as a human being to reach sexual maturity. While a single fish may carry million of eggs in its belly, the odds are that only a single hatchling will survive into adulthood,” according to Saffron.

These facts help to underscore just how much damage has been done in terms quality and quantity since the poachers—or brakanieri (buccaneers) as they’re called in Russia—took over. Netting any type of female sturgeon, no matter what age they are in order to meet a short-term quota has clearly done irreparable damage to the species; one report from 1996 estimates that there are only 1,800 mature sturgeon left in the Volga River. Compounding this travesty are the crude methods used to extract the eggs by inexperienced and unlicensed fishermen.

“Never make caviar from a dead sturgeon,” is one of the rules Saffron learns from the skilled masters known as the ikryanchik.

Being able to purchase this product in some run-of-the-mill grocery stores by the mid-1990s, American demand led to an explosion in counterfeit and smuggling operations. With a chapter titled “Caviar from a Suitcase,” there are some fascinating stories about Eastern Europeans arriving at JFK Airport with suitcases containing over $100,000 in caviar contraband. Even more revealing is one company that sold inferior paddlefish roe disguised as authentic caviar to American Airlines—whose customers and staff never noticed the difference. These illegal activities even went all the way up to reputable dealers like Hansen-Sturm, an offshoot of Dieckmann & Hansen, who along with Petrossian were the two most respected pillars of the international caviar trade.

It’s ironic that people would go to such lengths when for so many years caviar was considered to be simple peasant food. According to the book, Louis XV was so repulsed by it that he spit the eggs out onto the carpet at his Versailles palace. And when German entrepreneurs arrived in the United States to assess the Delaware River, which contained an abundance of sturgeon, they were shocked to see people using the roe as bait or to feed their livestock. Describing the early colonial experience, Saffron writes, “As these Europeans struggled to make their way in the wild land, it seemed that eating such a grotesque bottom-feeding fish as the sturgeon would be the equivalent of sinking into barbarism.” How times have changed.

Tracing this rich history, it appears that what is currently going on in the Caspian Sea is exactly what happened in both Germany and the United States. At one time, the port city of Hamburg on the River Elbe was rich in sturgeon. So was Penns Grove, New Jersey, who along with a nearby town aptly named Caviar, supplied more roe in the 1880s than any other place on earth. But due to a combination of overfishing and pollution, the caviar rush in both countries was very short lived. Could the Caspian Sea be next?

For many conservationists, the answer appears to be yes. Even though measures have been enacted to prohibit the importation of certain types of caviar (beluga caviar was banned outright in 2005), the future of sturgeon seems to be in North America and Western Europe where hatcheries have been established to prevent its extinction. In the decade following the book’s release, numerous facilities in Canada and the United States have sprung up in order to save the species. But the future in Russia seems very much in doubt. Despite surviving two world wars and a massive hydroelectric dam that once threatened their entire existence, the will to protect what was once a cherished part of Russian culture appears to be evaporating. Quoting one fisherman, he stated, “The U.S. couldn’t save the buffalo and we can’t save the sturgeon.”

You might also like:

|

|

|