By Joseph Temple

For countless decades, many Americans have viewed French cuisine as the undisputed gold standard of gastronomy. Of course, with visionaries such as Antonin Carême, Auguste Escoffier and Paul Bocuse combined with legendary restaurants like La Pyramide and Taillevent, it was pretty hard to dispute the notion of French supremacy over the culinary arts. “In France,” wrote Julia Child, “cooking is a serious art form and a national sport.”

But for many years, a disturbing trend has been occurring all across this great nation. Talented chefs have fled for greener pastures with numerous restaurants and wineries closing up shop for good. Even worse, the much-despised antithesis to haute cuisine, McDonald’s, became the country’s largest private sector employer in 2007. In less than thirty years, has France gone from a culinary mecca to a culinary backwater?

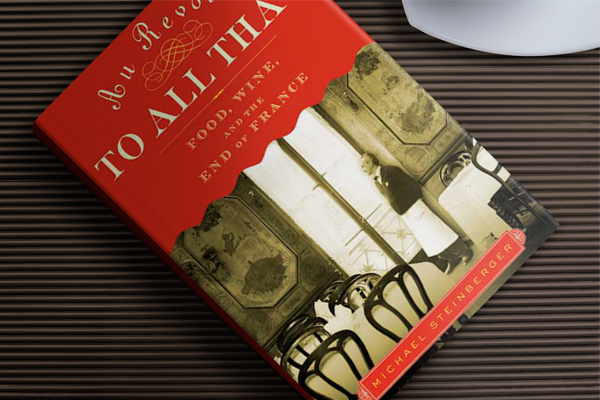

This is the controversial subject matter of Au Revoir To All That: Food, Wine, and the End of France by wine writer Michael Steinberger. First published in 2009, the author backs up his suspicions about the decline of French fare by speaking with an array of vintners, restaurateurs and industry experts who offer a stark contrast to the many myths surrounding French superiority. While many of us tend to look at France and its distinct culture with rose-colored glasses, Steinberger shows that the reality of the situation is very different.

Beginning in 1981 with the election of Socialist President François Mitterrand, the government’s transformative policies have had enormous consequences for restaurant owners and aspiring chefs. In order to fund the generous entitlement programs and a thirty-five-hour work week, harsh new taxes were created under Mitterrand. One such levy, known as the value-added tax (VAT) was set at a crippling 19.6 percent for restaurant bills, which also included a built-in 15 percent gratuity. These policies, the author contends, have forced many establishments to close their doors for good. “Chefs need prosperous patrons”, writes Steinberger. “Notwithstanding their other effects, the Reagan and Thatcher eras made the rich richer and spawned vast new wealth, money that bankrolled gastronomic revolutions in the United States and Britain. The French economy stagnated and French cuisine did likewise.”

With the balance of power shifting to other parts of Europe, and America, scores of French chefs have also left their native land—essentially becoming economic refugees. As home to approximately four hundred thousand expatriates, President Nicolas Sarkozy even joked that London has become “one of the great French cities”. But back in Paris, a huge labor shortage is occurring in restaurants and bistros, which is clearly affecting the food being served on your plate. Compounded by the fact that Spain and its la nueva cocina movement has placed that country at the culinary vanguard, Steinberger eloquently shows that France is clearly feeling the ramifications of left-wing policies now deeply embedded into their political culture.

Ironically, the law of unintended consequences has greatly benefitted the fast food industry, or what the French call la malbouffe. Having only a 5.5 percent VAT since they are considered “takeaway” establishments, restaurants like McDonalds have seen phenomenal growth with about a million customers per day, making France the second most profitable market for the American-owned hamburger chain. Appealing to a frugal population suffering from chronic unemployment, McDos has also been helped by the changing culture. “Younger French people today don’t understand or care about food. They are happy to gobble a sandwich or chips, rather than go to a restaurant,” said one restaurateur to Steinberger. “They will spend a lot of money going to a nightclub but not eat a good meal.”

In addition to these uncomfortable truths are the dim prospects for many French winemakers. With nearly half of all vineyards receiving appellation d’origine contrôlée (AOC) status by the mid-2000s, including many underserving one’s, some feel that this has diluted the country’s reputation for quality on the global stage. But it pales in comparison to the makers of vin de pays and vins de table wines, who are no longer protected by government subsidies. As part of France entering the EU, makers of these cheaper wines have been left to fend for themselves, especially in backwater regions like Languedoc, which has been hit particularly hard by this crisis. With domestic consumption in decline and stiff competition from countries like Argentina and Chile, the global demand for lower-end French wine is evaporating quickly. So while estates like Pétrus and Domaine de la Romanée-Conti have little to worry about with wine collectors across the world eagerly paying top dollar for their latest vintage, Steinberger reminds us that the gap between rich and poor is rapidly growing across France’s many vineyards.

Another fascinating chapter that makes this book a must-read is the story surrounding the world-famous Michelin guide. Considered a cherished bible for many restaurant-goers, its secret on what constitutes its highest honor—a three star rating—is closely guarded along with the recipe for Coca-Cola and Google’s SEO algorithm. However, many French restaurateurs have long suspected that the difference between two and three stars has nothing to do with the food on the plate and everything to do with décor. Requiring enormous sums of money to install fancy carpets, tablecloths and chandeliers, the result has been an increase in menu prices—a notion that doesn’t sit well with many owners who are dealing with a cash-strapped economy. Feeling the economic burden of having to satisfy anonymous Michelin inspectors instead of many potential customers, several chefs have even turned in their stars, opting instead for competitively priced dishes.

Discussing the many problems French cuisine faces as the twenty-first century kicks into high gear, Steinberger has written an exceptional book that raises a lot of serious questions for those who still think France is at the cutting edge of gastronomy. While some may disagree on the state of the country’s culinary future, it is important to note that during his research for this book, the author interviewed many prominent supporting figures. Bottom line: whether France is your native land, you have an interest in the culinary arts or are planning your next vacation to Paris, definitely pick up a copy of Au Revoir To All That.

You might also like:

|

|

|

The great French Michilin-starred restaurants, as well as the the many other excellent restaurants, bistros, etc, as a whole are just as good as they ever have been. But there is more to it than just the food. The atmosphere, the”attitude,” the “expectation and feeling of a great event,” the leisurely pace, the style, the civility, and yes, the decoration and atmosphere just seem to sweep you away into another world. And I love being there!

Wimberly