By Joseph Temple

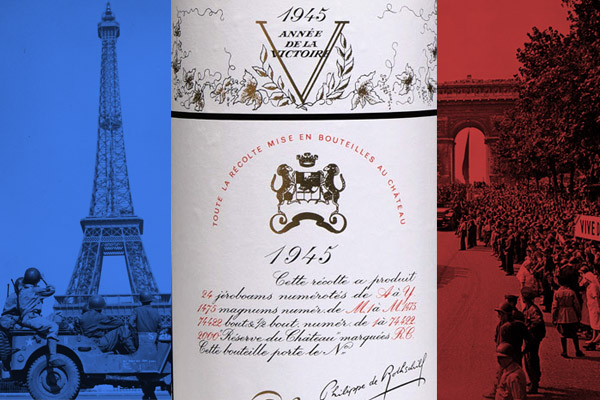

“Without doubt the greatest claret of the 20th century,” declared Decanter magazine. “Simply unmistakable” proclaimed Christie’s Michael Broadbent. “A consistent 100-point wine (only because my point scale stops at that number),” wrote Robert Parker. With endorsements like these, it was no surprise that a new world record was set in 2006 when a six-magnum case of 1945 Mouton Rothschild sold for a staggering $345,000. This, of course, begs the question:

What makes this particular bottle so valuable–and so memorable?

For the answer, you need to travel back in time to one of the darkest periods of the Second World War. After the fall of France, Bordeaux, with its close proximity to the Atlantic Ocean was of enormous value to Berlin, who wanted to avoid sending its submarines through the North Sea. And by 1943, the Kriegsmarine had built a massive U-boat base near the town, giving the German Navy direct access to Allied shipping routes. Of course, in addition to its geo-strategic importance, the region of Bordeaux, and its world-famous vineyards also became a prime target for exploitation—especially if a Rothschild owned them.

As the Wehrmacht began occupying the French coast, the Jewish-owned Château Mouton Rothschild would feel the effects of Nazi barbarism perhaps more than any other estate. Converting Mouton into a communications command center, nearly 4,000 pieces of art were stolen from the property while German soldiers regularly used family portraits on the walls for target practice, leaving the home riddled with bullet holes by the time of its liberation.

With its owner, Baron Philippe de Rothschild living in exile, the day-to-day operations of running the château were placed under the command of what the French scornfully called Weinführers—men whose job it was to purchase and ship the best wines back to Germany; there, they would be sold on the international market at a huge profit to help fund Hitler’s war machine. Assessing the entire French wine industry for bottles that could bring in a large infusion of hard currency, a key area of interest became Bordeaux, which included Mouton, a notable second growth.

Fortunately for the Bordelais, their Weinführer stood in stark contrast to the actions of many soldiers in the region. Heinz Bömers, although employed by the Third Reich, had been a wine importer long before the war and on good terms with many vintners in Bordeaux. “Let us try to continue our business as normally as possible,” he would tell the community at large. And to prove he had their interests at heart, Bömers would do his best to save the most valuable vintages from Nazi pillaging.

One memorable story told in Don and Petie Kladstrup’s book Wine & War involves Château Mouton Rothschild and Hermann Göring. Despite its Jewish ownership, the Field Marshal absolutely loved the wines from Mouton, demanding that numerous cases be shipped to his Carinhall estate. Bömers however despised Göring, instructing French winemakers to fill them with vin ordinare instead. All these efforts during this difficult time would not go unnoticed by Baron Philippe de Rothschild, who agreed to let the ex-Weinführer represent Mouton in Germany after the war.

The liberation of Bordeaux, August 28, 1944. Musée d’Aquitaine.

The liberation of Bordeaux, August 28, 1944. Musée d’Aquitaine.

With the liberation of Bordeaux in August of 1944, Rothschild came back to his beloved château, vowing to rebuild the empire he helped to create. Despite living in a state of chaos where wires were cut and telegraph poles were down throughout Pauillac, Mouton’s 1945 harvest proved to be something extraordinary, leading to a vintage that became the envy of all his first-growth competitors.

After an unusual frost in early May, the dry and humid summer that year would lead to some very ripe grapes and an alcohol content approaching 15%. Describing the situation, Decanter magazine wrote, “The vineyard had not been renovated for some years, although this was probably an advantage, since it increased the proportion of old vines in the 1945. The wine would have been fermented in large wooden vats, but there would have been few, if any, new oak barrels in the cellar.” Over time, all these factors would lead to “power and spiciness [that] surge out of the glass like a sudden eruption of Mount Etna: cinnamon, eucalyptus, ginger… impossible to describe but inimitable, incomparable,” according to Michael Broadbent.

For many collectors, the bottle’s iconic label turned out to be just as important as what was inside the bottle. Since taking over the estate, Rothschild proved to be a gifted marketer, introducing a number of firsts in the industry. Unlike other wineries that shipped their product in bulk to merchants who then stored it, Mouton would be the first in Bordeaux to do what was called château bottling. This allowed him to distinguish his product from the plethora of lower quality wines, thus increasing the value of the brand. For the first vintage under this new system, Rothschild would commission artist Jean Carlu to design the label that included his now famous signature—something very unique at the time. But for Mouton’s first bottles of the post-war world, a powerful reminder of what Europe had just endured was urgently needed.

In addition to Winston Churchill’s famous V for Victory, French illustrator Philippe Jullian would add the inscription “Année de la Victoire” to this now famous label. With people celebrating in the streets throughout western Europe, the marketing campaign proved to be just as flawless as the wine itself, making Mouton the unofficial wine of Allied triumph. It was so successful that every year since 1945, Rothschild has commissioned a different artist to design the label from Pablo Picasso to Andy Warhol, making these wines the Holy Grail for collectors.

For Baron Philippe de Rothschild, victory inevitably led to vindication when in 1973 Mouton was upgraded to a first-growth. The only change ever to Bordeaux’s original 1855 Classification, this decision also changed the chateau’s motto to Premier je suis, Second je fus, Mouton ne change. (“First, I am. Second, I used to be. Mouton does not change.”) In less than a thirty-year time span, Mouton had rose to the top by capturing the attention of oenophiles across the world.

More than seventy years since V-E Day, the 1945 Mouton Rothschild has come to symbolize much more than what Robert Parker calls “truly one of the immortal wines of the century.” The perseverance of Rothschild and his winemakers to harvest the greatest vintage of the century despite the enormous obstacles is truly remarkable. But even more impressive was Rothschild’s ability to rebuild an empire stolen from him, making it even stronger in such a short period of time. As he would tell the former Weinführer Heinz Bömers who asked to represent the estate in post-war Germany: “Yes, why not. It is a new Europe we are building.”

Sources:

Coates, Clive. Grands Vins: The Finest Châteaux of Bordeaux and Their Wines. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.

Davis, Charlotte Williamson. 101 Things to Buy Before You Die. London: New Holland Publishers, 2007.

Kladstrup, Don and Petie. Wine & War: The French, the Nazis & the battle for France’s greatest treasure. New York: Broadway Books, 2002.

Meltzer, Peter (2006, Oct 2). Christie’s Shatters Auction Record Twice. Wine Spectator. Retrieved from http://www.winespectator.com

Rothschild, Hannah. The Baroness: The Search for Nica, the Rebellious Rothschild. New York: Random House, 2012.

Siler, Julia Flynn. The House of Mondavi: The Rise and Fall of an American Wine Dynasty. New York: Gotham Books, 2007.

1945 Mouton-Rothschild, Pauillac. K&L Wine Merchants. Retrieved form http://klwines.com

Wine Legends of 2011: Château Mouton Rothschild 1945 . Decanter. Retrieved from http://www.decanter.com

You might also like:

|

|

|