By Joseph Temple

For most Americans, President Thomas Jefferson is remembered as a key author of the Declaration of Independence and the main architect behind the Louisiana Purchase. Oenophiles however view Jefferson as a trailblazer for American viticulture, strongly advocating for quality wines produced inside the United States. “No account of the history of wine in America is complete without at least a bare summary of ‘Jefferson and wine,’” wrote historian Thomas Pinney.

Experiencing the best that Europe had to offer during his time as the American Minister in Paris and later as the first Secretary of State, Jefferson firmly believed that this winemaking expertise could successfully cross the Atlantic. “We could, in the United States, make as great a variety of wines as are made in Europe, not exactly of the same kinds, but doubtless as good.” More than two hundred years later, this statement has come to fruition as vineyards across America – from Jefferson’s home state of Virginia to the Napa Valley – compete with the best from around the world.

And in honor of his pioneering efforts, we present eight historical footnotes on President Jefferson and his passion for wine:

When it came to wines during the pre-revolutionary period, men of privilege drank either Madeira or Port – the result of what Jefferson described as “our long restraint under the English government to the strong wines of Portugal and Spain.” So how did this man develop a liking for the wines of Italy and France, which would have been highly unusual at the time? Many biographers point to his mentor George Wythe who befriended Jefferson while he was studying law in Williamsburg and the person who most likely introduced him to the wines of Bordeaux. Another possible influence were the Hessians – Germanic mercenaries fighting on the side of Britain during the American Revolution – who exposed Jefferson to the wines of their native lands after being captured in Virginia.

blank

Throughout the thirteen colonies, Americans had a strong affinity for alcohol. In fact, during colonial times there were more taverns per capita than any other business. Unfortunately, this resulted in everything from bar room brawls to broken homes, eventually giving birth to the Temperance Movement. But instead of prohibition, men like Thomas Jefferson proposed another solution to combat the problems caused by whiskey and other high-alcohol spirits. “No nation is drunken where wine is cheap; and none sober where the dearness of wine substitutes ardent spirits as the common beverage. It is, in truth, the only antidote to the bane of whiskey,” wrote Jefferson.

blank

On a mountaintop near Charlottesville, Virginia stands Monticello – a UNESCO World Heritage Site and home to America’s first commercial vineyard venture. The story begins in November of 1773 when an Italian physician named Philip Mazzei was searching for the perfect spot to make wine. Stumbling upon this neo-classical home, Mazzei and Jefferson met and discussed the idea of growing European rootstocks on Virginian soil. Jefferson was so impressed that he gave Mazzei 193 acres on the south side of Monticello for forming “a Company or Partnership, for the Purpose of raising and making Wine, Oil, agruminous Plants, and Silk.” Although the partnership would be derailed by both frost and a revolution, the idea that wine could thrive in the Commonwealth of Virginia was more than two hundred years ahead of its time.

blank

By Frederick Wildman and Sons, Ltd [CC BY-SA 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

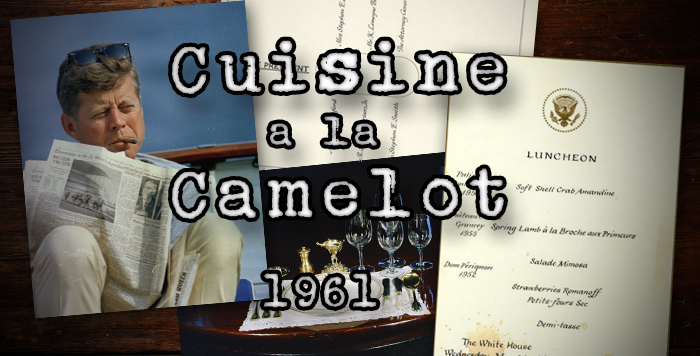

As a diplomat sent to Europe by the Confederation Congress, Thomas Jefferson would have the opportunity to taste many wines during his stint as Minister to France. He absolutely loved Champagne and while in Burgundy, he was partial to the vineyards of Chambertin. But his all-time favorite were white Hermitage wines from northern Rhône. A region known more for its Syrah, Jefferson described white Hermitage as “the first wine in the world without a single exception.” He was enthralled with it so much that during his presidency, the oenophile-in-chief ordered five hundred bottles to be placed in the White House wine cellar.

blank

Back when the White House was known as the President’s House, nobody knew how to throw a party like Thomas Jefferson. During his eight years in office, over 20,000 bottles were purchased from Europe and in less than a fourth-month period, over 200 bottles of Champagne were consumed at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. With an annual salary of $25,000 that included entertainment expenses, Jefferson threw financial caution to the wind by spending over $7,000 on wine in his first term alone. Author James Gabler writes, “his expenditures for food and wine ran a footrace with his income. Income usually lost.”

blank

Being an oenophile in the early 1800s – especially one who preferred wines from France – was a struggle to say the least. Any bottle you ordered could easily break or spoil on the long voyage across the Atlantic Ocean. And if there wasn’t the constant threat from pirates who might raid the ship, sailors and boatmen could easily finish the wine and refill it with water by the time it reached the unsuspecting shores of America. Knowing all these variables, Jefferson invested an enormous amount of energy in making sure his product arrived safely and in tact. John Hailman in Thomas Jefferson on Wine writes, “Jefferson had to specify in each letter the ship, the captain, the ports of exit and entry, how the wine should be packaged, and how he would get payment across the ocean … that he took such pains shows just how much he desired fine wine.”

blank

When President James Madison declared war against the British in 1812, one of the biggest advocates for military action was Thomas Jefferson who said it would take “a mere matter of marching” before the United States conquered all of Canada. But as the War of 1812 turned into a two-and-a-half year stalemate, the prolonged battle against the greatest navy in the world would leave this ex-president high and dry. With his suppliers from France cut off, Jefferson would tell a wine merchant that war with Britain “at length left me without a drop of wine.”

blank

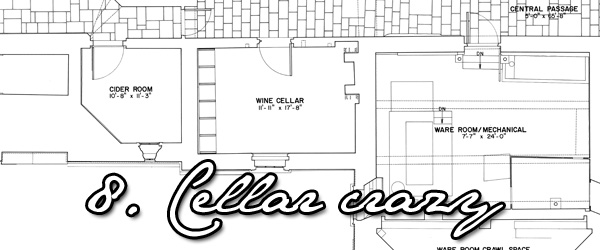

In today’s world, having just one wine cellar is cause for celebration. But can you believe that Thomas Jefferson possibly had over a dozen! Between his two at Monticello, one at the Virginia Governor’s Mansion, two at the White House and numerous others from Philadelphia to Paris, Jefferson wasn’t very far from his collection of wine. And while you can still see his cellar at Monticello, the one at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue was lost forever when British troops burned the entire building to the ground in 1814.

blank

Sources:

Craughwell, Thomas J. Thomas Jefferson’s Creme Brulee: How a Founding Father and His Slave James Hemings Introduced French Cuisine to America. Philadelphia: Quirk Books, 2012.

Gabler, James M. Passions: The Wines and Travels of Thomas Jefferson. Baltimore: Bacchus Press Ltd., 1995.

Hailman, John. Thomas Jefferson on Wine. The University Press of Mississippi, 2006.

Taber, George. Judgement of Paris: California vs. France and the historic 1976 Paris tasting that revolutionized wine. New York: Scribner, 2005.

Wallace, Benjamin. The Billionaire’s Vinegar: The Mystery of the Most Expensive Bottle of Wine. New York: Three Rivers Press, 2009.

You might also like:

|

|

|