On Sunday morning, a 6.0-magnitude earthquake hit the San Francisco Bay Area and the surrounding region, injuring hundreds of people and leaving thousands without water and electricity. There have thankfully been no deaths due to this natural disaster, but an area hit particularly hard is Napa, home to a $13 billion dollar a year wine industry. According to one report, 33 buildings have been declared unsafe to enter with another 600 properties experiencing water and sewage problems. The biggest earthquake to hit the Northern California since 1989, the total economic damage is estimated to be in the billions.

For anyone living in the areas affected by this earthquake, two Red Cross evacuation centers are open to those in need – one at the Crosswalk Community Church in Napa at 2590 First Street and another at the Florence Douglas Center at 333 Amador Street in Vallejo. For those in the wine industry, you can visit Napaearthquake.com, where numerous individuals have offered their help and assistance.

At the International Wine & Food Society, our best wishes go out to the people of the Golden State. And if history is any indication, we are confident the region will only emerge stronger from this disaster.

One hundred and eight years ago, the epicenter of California’s wine industry was not in the vineyards of Napa or Sonoma, but in the city of San Francisco. With its close proximity to both railroad lines and shipping routes, the Bay Area became an important hub during a time when merchants were in control of both production and distribution. Firmly entrenched in the city was the powerful California Wine Association (CWA), which controlled nearly 75% of the market as “the distinction between winegrower and wine merchant was not sharply drawn.” According to historian Thomas Pinney, “their [the CWA’s] produce was sent to central cellars in San Francisco where the wines were stored, blended to a uniform standard, bottled, and then shipped for sale … as a monopoly, or rather, near-monopoly, it belonged to the rapacious business style of the late nineteenth century, and, no doubt, if the full record could be known it would show a long tale of sharp practices and dubious moves.”

However, this dominant organization would be rendered helpless on April 18, 1906, when a 7.8-magnitude earthquake rocked San Francisco to its core. With over 28,000 buildings destroyed, 3,000 deaths and half the city left homeless, it is to this day one of the worst natural disasters in American history.

And while some people tried to save their wine from the destruction, in some cases, it was wine that was saving them.

Silent film documenting the aftermath of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

Courtesy: Prelinger Archives

With fires spreading throughout the Bay Area and the water supply shut off due to the intense shaking that ruptured nearly 30,000 city pipes, wine became an important weapon to combat the roaring flames. Luckily, thousands of recent immigrants who successfully fought against statewide prohibition, had homemade wine operations that proved useful in saving San Francisco from total ruin. “In those days, many Italian immigrants fermented wine in their basement and there are stories of old-timers getting them out and pouring them on the fire,” declared one resident.

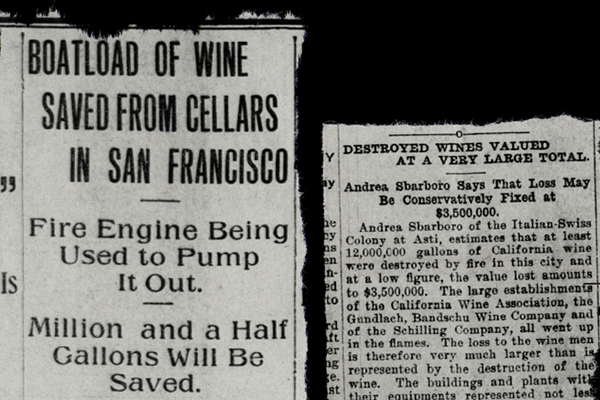

At CWA headquarters, efforts were made to salvage whatever they could of its enormous stockpile. Using a city-owned fire engine, a million and a half gallons of wine was pumped out from one of their still burning cellars and placed into a barge where it was then distilled into brandy. Still, the CWA lost approximately 10,000,000 gallons due to the earthquake, while its competitor, the Italian Swiss Colony (a company also located in the area) lost over 12,000,000 gallons and roughly $3,500,000 (over $88,000,000 in today’s dollars) in damages to their building and the equipment inside it.

Newspaper articles reporting on the disaster.

Credit: California Digital Newspaper Collection.

In the aftermath of this devastating disaster, the wine industry learned a painful lesson on the dangers of centralization. W. Blake Grey of the San Francisco Chronicle writes, “With their headquarters and most of their wine destroyed, wineries moved their operation closer to the grapes, and thus what we now think of as Wine Country was also changed forever.” Remarkably, after just a few years of restructuring, the California wine industry successfully rebounded from this devastating loss.

Whether an earthquake, phylloxera, numerous droughts, two economic depressions or thirteen painful years of prohibition, the Golden State and its wine have clearly faced numerous challenges over the past century. Yet after each of these catastrophic events, California fights back, becoming an undisputed leader around the globe for quality wine. If history is any indication of the resilience of Californians and their wine industry, they are sure to overcome this most recent devastation and maintain their world class designation.