In 2005, China drastically lowered its tariffs on imported wines from 64% to 14%. Since then, scores of buyers have made up for lost time by indulging themselves in the fine art of wine tasting — a practice that Chairman Mao’s Cultural Revolution outlawed for being decadent and bourgeois. Now seldom does a week go by without a news story discussing the impact China is having on wine exports. Purchasing 1.86 billion bottles in 2013 (a 136% increase in only five years), a whole new generation of oenophiles are springing up from Shanghai to the Himalayas as winemakers around the world eagerly look to cash in.

But what about China’s domestic production? Since almost 95% of the wine consumed in the People’s Republic comes from locally grown grapes, perhaps its time to have a closer look at this potential vino-superpower.

Having a largely superstitious population, it’s no surprise that red wine dominates the marketplace. That’s because the color red is considered lucky in Chinese culture, while the color white is synonymous with death. Unfortunately, since the majority of its wine consists of local grapes blended with cheap bulk wine imports, even their finest Cabernet is no match against France or California in terms of quality. That’s why a sort-of Sino-Franco alliance has been established in recent years.

Beginning in 1978 when China first opened its doors to the West, an influx of foreign wine producers have partnered with government-run businesses to help improve the quality of its vineyards. Some of these joint ventures have been with notable vintners such as Rémy Martin, Pernod-Ricard and more recently in 2009 when Domaines Barons de Rothschild (DBR) Lafite partnered with China’s biggest state-owned investment company to produce wine geared towards the domestic market.

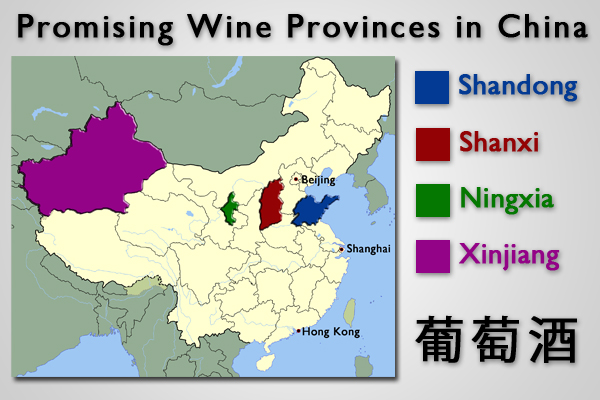

Setting up shop in the city of Penglai, DBR, like most winegrowers chose the Shandong Province as their hub, which along with the Province of Shanxi benefits from a maritime climate. Located northwest of Shanghai and south of Beijing, these two provinces share the same latitude as California and would be almost Mediterranean in climate if it weren’t for the raging monsoons. Of the approximately 500 wineries in China, the majority are located in these two provinces, but that doesn’t mean that there aren’t others that are emerging as well, such as the Mount Helan region and Xinjiang Province on China’s western border.

As of today, Chinese wine has still failed to reach a global audience. But working alongside established vintners to increase quality, the People’s Republic might just be a sleeping giant ready to dominate the global marketplace. Just remember that fifty years ago, wines from Australia and California were held in similar contempt.