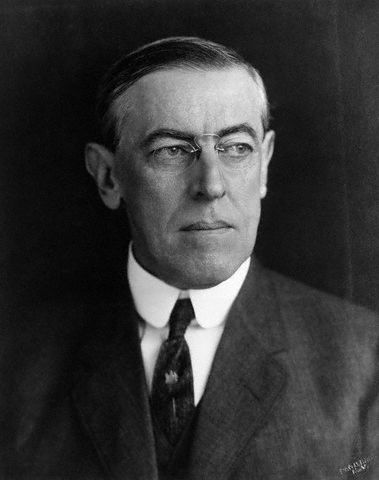

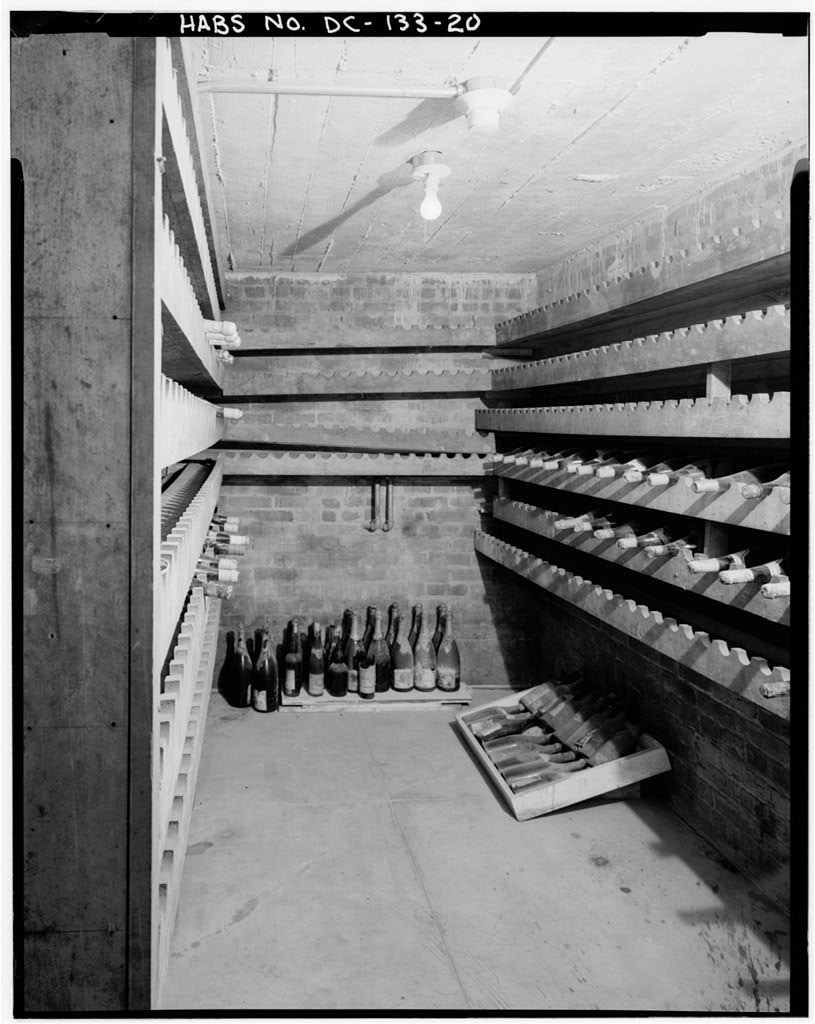

(Left) President Thomas Woodrow Wilson. (Right) Wilson’s wine cellar at 2340 S St NW, Washington, DC. Photos courtesy Library of Congress. (click to enlarge)

(Left) President Thomas Woodrow Wilson. (Right) Wilson’s wine cellar at 2340 S St NW, Washington, DC. Photos courtesy Library of Congress. (click to enlarge)

By Joseph Temple

A great show to check out on the History Channel is 10 Thing You Don’t Know About, a documentary series that uncovers little-known facts about popular historical subjects. And during a recent episode dealing with the topic of prohibition, viewers were given a fascinating tour of President Woodrow Wilson’s private wine cellar. According to the historian interviewed on the program, the collection was moved directly from the White House to Wilson’s home at 2340 S Street in Washington DC as he left office in March of 1921. But with prohibition in effect – and the transportation of alcohol illegal – the ex-president was given a special exemption by Congress to move his vast collection to what is now known as Woodrow Wilson House, a U.S. National Historic Landmark.

Reading Garrett Peck’s Prohibition in Washington D.C.: How Dry We Weren’t, the author notes that Wilson’s collection included many bottles of Champagne and Bordeaux from the 1920s which were probably given to him and his wife by Parisian diplomats working on Embassy Row in D.C. In fact, fellow Treaty of Versailles architect and former French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau visited Wilson during his three-year stay on S Street. Of course, being the good house guest, Clemenceau most likely brought a few bottles with him as a present for his gracious hosts!

Occupying the lowest room of the entire house, the president’s wine cellar symbolizes the many double standards of the prohibition era. While the country’s poor risked prosecution for the mere consumption of alcohol, Wilson along with numerous manor-born politicians and wealthy elites acted as if the laws didn’t apply to them – and in most cases they didn’t. Having a bottle in one hand and an Anti-Saloon League membership card in the other, many in Congress violated in private the policies they advocated for in public. In fact, the reason why Wilson became so adamant in moving his collection from 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue was out of fear that his successor Warren Harding – a staunch supporter of the temperance movement — would drink it all.