By Marc A. Cormier – www.st-pierre-et-miquelon.com [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

By Joseph Temple

Given to France as a consolation prize following her defeat on the Plains of Abraham, few could imagine that St. Pierre and Miquelon—a string of tiny islands near the coast of Newfoundland—would turn into some of the most valuable real estate on earth during the 1920s and early 1930s. That’s because once the United States enacted the flawed policies of prohibition, this territory of ninety-three square miles instantly morphed into a lucrative hub for smuggling liquor into North America. For nearly thirteen years its small and remote population experienced a period of unprecedented economic prosperity supplying alcohol to their dry neighbors. And chances are that if you or anyone you knew drank wine, champagne or hard liquor during that time, it probably passed through this little-known gangster’s paradise.

Looking at a map, France’s smallest colony was a dream come true for both bootleggers and suppliers. Situated just fifteen miles off Canadian shores and only a short distance from the largest Rum Row that supplied the American northeast, St. Pierre and Miquelon had a distinct geographical advantage. But more importantly, it was French law that governed the islands, making it legal to drink, produce, store and transport everything from Bordeaux to Bourbon on this strategic outpost. So when the Volstead Act took effect on January 1, 1920, these beneficial laws began attracting the attention of everyone from Samuel Bronfman to Al Capone.

In addition to French wine exports already arriving on the islands, distillers of Canadian whiskey determined to sell their product south of the 49th parallel quickly turned this archipelago into their own personal fiefdom. Already enticed by its deep-water ports that allowed boats to dock year round, the clear financial benefits made it an easy decision for these liquor kingpins. Charging a mere four-cents-per-bottle as an import tax, it was less than one-tenth of its biggest offshore competitor, the Bahamas. On top of that was the ease in acquiring international landing certificates required by Ottawa in order to be exempt from paying duty on exported liquor. Historian Daniel Okrent writes, “St. Pierre lay just fifteen miles off Canadian sores, but for duty purposes it was as foreign as the Congo. No longer did Canadian distillers have to supply their agents in Havana and other distant ports with wads of cash required by local officials before they would stamp fake landing certificates.”

A map of Atlantic Canada from the 1700s showing St. Pierre & Miquelon.

Almost overnight, the entire colony experienced prosperity like never before as a prime liquor hub for much of North America. The French government spent close to 20 million francs to improve its harbor and storage facilities, which were now accommodating a thousand ships each year. Despite its low import duties, income from customs alone was three times the operating budget of St. Pierre & Miquelon before prohibition. Gangsters in pinstriped suits and fedora hats could be seen wandering around L’Hotel Robert, including Al Capone who was rumored to have a private residence on the island. And with more than two million gallons of Canadian whiskey being exported in just one year, a branch of the Canadian Bank of Imperial Commerce was established on the territory. Considering the Dominion was doing more business there than they were with Argentina, Australia, Ireland or China, it wasn’t a bad decision at all.

Of course, getting the alcohol to St. Pierre was the easy part. Illegally exporting it to the United States was the dangerous job left to rum runners who risked arrest and seizures if caught by American customs officers. One famous bootlegger who visited St. Pierre and Miquelon frequently was Bill McCoy (a.k.a. The Real McCoy) who battled not only high-speed pursuit boats but also potential hijackers once his ship, the Sable Island departed for the east coast. Thankfully helping him and others every step of the way were locals armed with secret radio transmissions and years of experience navigating vessels. After all, it was their financial futures that lay in getting as many bottles as possible to U.S. soil.

Locals and rum runners loading a ship with what appears to be wine on St. Pierre.

Locals and rum runners loading a ship with what appears to be wine on St. Pierre.

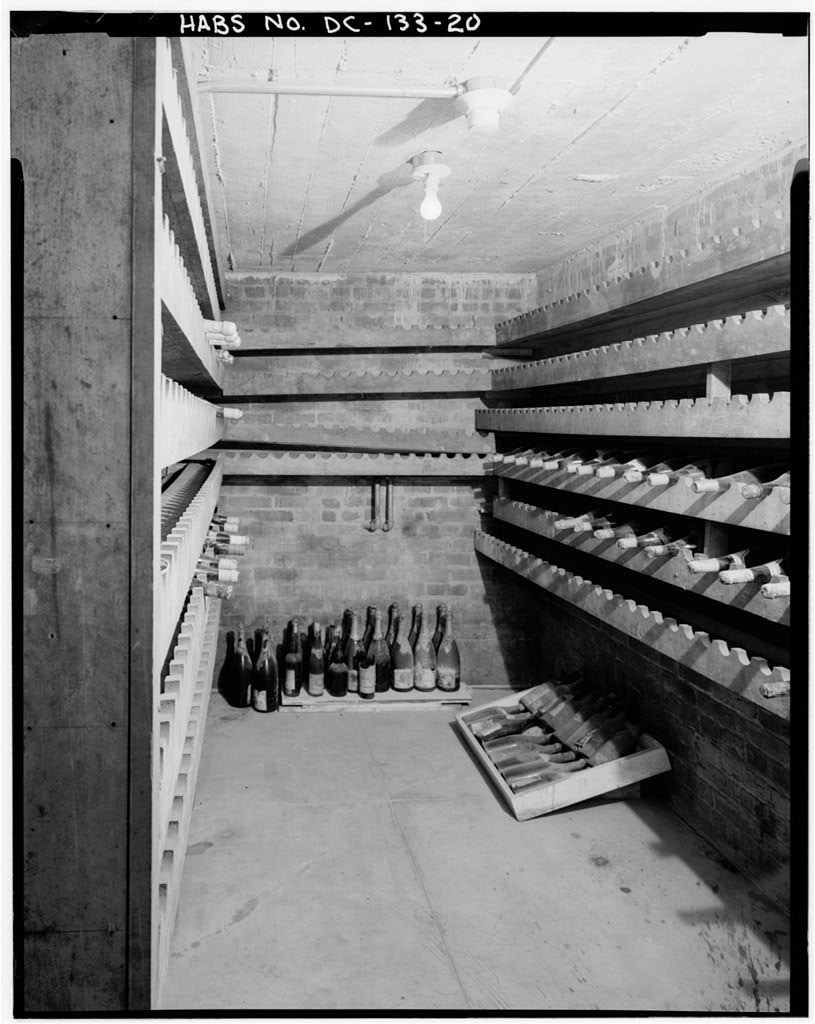

For the more than three thousand people who lived on the islands, the rising economic tide was lifting all boats. Despite a massive construction boom, the storage facilities were still inadequate, causing liquor companies to pay private homeowners for use of their basements to stockpile nearly four million bottles of either champagne or whiskey at any given time. The liquor trade was so profitable that most residents who had previously made a living as fishermen were now either living off the easy money or making even more by transporting the alcohol along with the likes of McCoy and the other bootleggers. But it wasn’t like they had any choice—the refrigeration plants used to store fish had been converted into liquor warehouses.

Unfortunately, what goes up must eventually come down.

Just as the economic miracle of St. Pierre & Miquelon rose to new heights with the enactment of prohibition, it would burst even more quickly after repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment in 1933. With America reverting back to a wet nation, the demand dried up almost overnight on the islands, causing a massive depression that was to be felt for years to come as both gangsters and Canadian bankers left for greener pastures. Even today, despite a more diversified economy coming from tourism and oil and gas exploration, the archipelago hasn’t experienced a boom like they did during those thirteen years. Never again would St. Pierre according to Canadian historian Peter C. Newman be “buried in an avalanche of freight, pungent with the smell of superior liquor … so strong that at times the fog that rolled up St. Pierre’s steeply inclined streets with the nightly tides would carry a distinct Scotch flavour.”

Sources:

Anglin, Douglas G. The St. Pierre and Miquelon “Affaire” of 1941: A Study in Diplomacy in the North Atlantic Quadrangle. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1966.

Hunt, C.W. Booze, Boats & Billions: Smuggling Liquid Gold. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1988.

Okrent, Daniel. Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition. New York: Scribner, 2011.

Schneider, Stephen. Iced: The Story of Organized Crime in Canada. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2009.

You might also like:

|

|

|